The 60/40 portfolio—60% stocks, 40% bonds—used to be the default answer to every allocation question. Simple, elegant, Nobel Prize-backed. Stocks generated growth, bonds provided ballast when markets got rough. Financial advisors loved it. Retirement savers trusted it. The whole thing just worked.

Until 2022 proved it didn't.

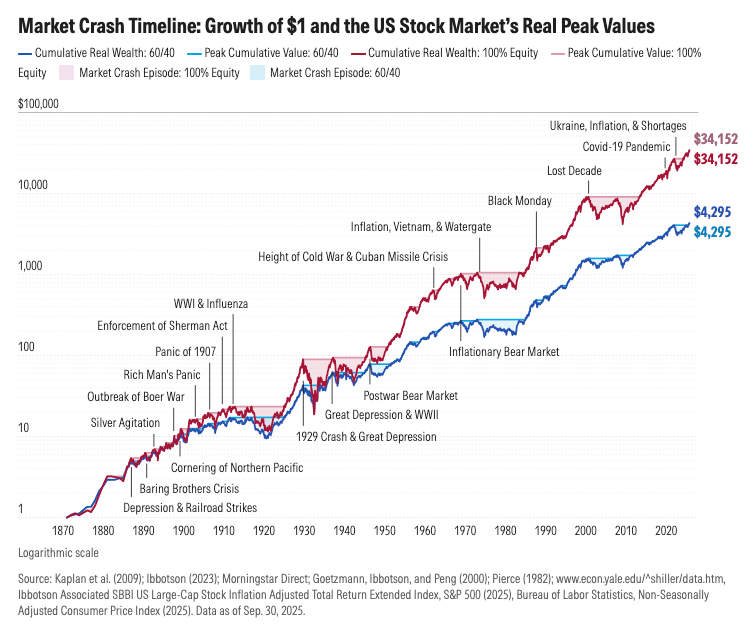

That year delivered what Cambria Investment Management's Meb Faber called "likely the worst year ever for a traditional 60/40 portfolio on an after-inflation basis." Both stocks and bonds fell together. The supposed diversification benefit evaporated precisely when it mattered most. Investors who thought they were protected discovered they'd been caught in a trap of their own making.

Meanwhile, walk into any serious family office today, and the portfolios look nothing like the textbook model. More real estate. More private equity. More direct lending. Barely any bonds. The wealthy figured out years ago what the rest of the market is only starting to understand: the assumptions that made 60/40 work have fundamentally changed.

Key Takeaways

- The 60/40 portfolio delivered its worst inflation-adjusted returns since the Great Depression in 2022—both stocks and bonds fell together when protection mattered most

- Correlation flipped: Stock-bond correlation shifted from -0.37 to +0.60—the diversification benefit that justified 40% in bonds has fundamentally broken

- Family offices rebuilt: US family offices now hold just 9% in fixed income, 27% in private equity, and 54% total in alternatives

- Yield gap is massive: Private credit delivers 10%+ gross returns vs 4-5% Treasuries. After taxes for high earners: 6% vs 2.7%

- Tax efficiency compounds: Real estate depreciation, 1031 exchanges, and stepped-up basis at death can eliminate capital gains entirely across generations

- Access has democratised: BDCs, interval funds, and non-traded vehicles now let founders access private credit with minimums as low as $2,500-$25,000

- Watch the fees: Private market fees of 2%+ management plus 20% carry compound relentlessly—a 15% gross return becomes 10% or less after costs

- Concentration kills: Archegos lost $20B in 48 hours through leveraged, concentrated positions—diversification within alternatives matters as much as across them

- Geographic diversification is the often-missed dimension—founders who built global businesses should extend that mindset to personal wealth

What Happened in 2022

To understand why HNW investors abandoned the traditional model, it helps to examine what went wrong.

The theory behind 60/40 rests on correlation. When stocks fall, bonds typically rise (or at least hold steady). Harry Markowitz won a Nobel Prize for formalising this diversification benefit in the 1950s. For decades, it delivered exactly as promised.

The relationship held through the dot-com bust, through the 2008 financial crisis, even through the initial COVID shock in 2020. Bonds did their job.

Then inflation returned. The Federal Reserve responded with its most aggressive rate-hiking cycle in over 40 years. And the correlation that had protected portfolios for decades suddenly flipped.

According to State Street research, the stock-bond correlation spiked to +0.60 in recent years—compared to -0.37 over the prior decade. A Morningstar analysis found that 2022 was "the one year in our whole 150-year period in which bonds didn't provide any diversification benefit during a market downturn."

The numbers tell the story: US equities dropped roughly 19%, while the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index fell approximately 13%. It was the worst joint performance for the pair in over four decades. A globally diversified 60/40 portfolio declined about 16-17%, making it one of the worst calendar-year performances in modern history.

The whole premise of the allocation model failed at the worst possible moment.

How Family Offices Invest Now

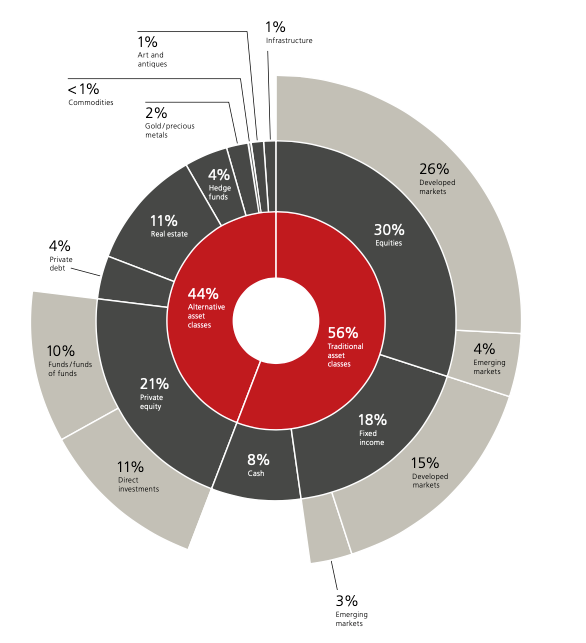

The UBS Global Family Office Report 2025 surveyed 317 family offices managing an average of $1.1 billion each. Their average family net worth sits at $2.7 billion. These aren't small operations guessing at allocation strategies—they're sophisticated investors with dedicated teams and access to opportunities most people never see.

Their portfolios look radically different from what traditional advisors recommend.

Family Officsa global asset allocation breakdown for 2024:

Alternatives now represent 44% of the average family office portfolio globally. But those global averages mask significant regional variation. American family offices lean even more heavily into alternatives—54% in alternatives, with 27% in private equity alone and 18% in real estate. Traditional fixed income represents just 9% of US family office portfolios.

That's not a tweak to the 60/40 model. That's a complete overhaul.

The Allocation Shift: From Traditional to Modern

| Asset Class | Yale 1989 | Global Family Offices 2024 | US Family Offices 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Equities | ~65% | 26% | 32% |

| Fixed Income | ~25% | 18% | 9% |

| Cash | ~5% | 8% | 5% |

| Real Estate | ~5% | 11% | 18% |

| Private Equity | — | 21% | 27% |

| Hedge Funds | — | 4% | 3% |

| Private Credit | — | 4% | 3% |

| Other Alternatives | — | 8% | 3% |

Sources: Yale Endowment historical data; UBS Global Family Office Report 2025

Case Study: From Exit to Allocation Overhaul

Consider the case of a SaaS founder we'll call Marcus. After selling his B2B software company for $28 million in 2021, he followed his wealth manager's advice and parked the after-tax proceeds—roughly $19 million—into a standard 60/40 portfolio. Diversified index funds, investment-grade bonds, the whole conventional package.

By December 2022, Marcus had lost over $3 million on paper. Both sides of his portfolio declined together. The bonds that were supposed to protect him fell nearly as hard as his equity allocation.

The wake-up call prompted a complete rethink. Over the following 18 months, Marcus restructured his portfolio entirely:

- Public equities dropped to 35% (from 60%), with a tilt toward dividend-paying for investors with serious capital anymore

- Private equity rose to 20% through two fund commitments and three co-investments in enterprise software—a sector he understood deeply from his operating days

- Real estate climbed to 18% via a mix of directly held multifamily properties and two private real estate funds

- Private credit reached 12% through a publicly traded BDC and an interval fund focused on senior secured lending

- Cash and short-term instruments held at 15% for opportunistic deployment

The shift wasn't about chasing returns. It was about building a portfolio that made sense for his actual situation: a long time horizon, no need for liquidity beyond a reasonable buffer, deep expertise in software businesses, and a desire to stay engaged with interesting companies rather than passively watching index funds fluctuate.

Two years into the new allocation, Marcus reports something more valuable than the performance numbers: he actually understands what he owns. The operating experience that made him wealthy in the first place now informs how he deploys capital.

Why Bonds Got Demoted

Bonds served two purposes in traditional portfolios: income and protection. Neither function works particularly well for investors with serious capital anymore.

On the income side, even with yields higher than they've been in years, the math doesn't work for wealth building. A 10-year Treasury might offer 4-5% nominal yield. After taxes and inflation, the real return barely keeps pace.

On the protection side, 2022 demonstrated the limits clearly. When both stocks and bonds fall together, the supposed hedge provides no cushion.

Private debt has essentially replaced bonds in sophisticated portfolios. According to Morgan Stanley research, direct lending returned 10.5% annualised in Q4 2024, beating both high-yield bonds and leveraged loans. During seven periods of rising rates since 2008, returns in direct lending averaged 11.6%—two percentage points above its long-term average.

KKR's Global Head of Private Credit noted that investors can now achieve "10%+ gross return on an unlevered basis" for senior-secured risk. That's double or triple what comparable bond allocations might generate.

Tax Efficiency Advantage

Beyond raw returns, alternative investments often carry significant tax advantages that amplify their edge over traditional bonds.

Real Estate Depreciation

Rental property owners can deduct depreciation—a non-cash expense that reduces taxable income without affecting actual cash flow. Residential properties depreciate over 27.5 years, commercial over 39 years. A $1 million rental property might generate $36,000 in annual depreciation deductions, sheltering an equivalent amount of rental income from immediate taxation.

Cost segregation studies can accelerate this further, front-loading depreciation into earlier years when the tax shield provides maximum benefit.

1031 Exchanges

Section 1031 of the Internal Revenue Code allows real estate investors to defer capital gains taxes indefinitely by exchanging one investment property for another of "like kind." Sell a $2 million apartment building with $800,000 in gains, and those gains roll tax-free into the replacement property—as long as strict timelines and rules are followed.

The real power comes from chaining exchanges throughout a lifetime. Each transaction defers the prior gains. Upon death, heirs receive a stepped-up basis that can eliminate the accumulated deferred taxes entirely. A $500,000 gain that would have triggered $150,000+ in taxes simply disappears through proper estate planning.

Private Credit Tax Treatment

Interest income from private credit is typically taxed as ordinary income—no better than bonds. But the higher gross yields often more than compensate. A 10% yield taxed at ordinary rates still beats a 4.5% Treasury yield after the math is done.

Many investors also access private credit through tax-advantaged accounts where possible, capturing the higher yields while deferring or eliminating tax drag.

After-Tax Comparison

For a high-income investor in a 40% combined marginal bracket:

| Investment | Pre-Tax Yield | After-Tax Yield |

|---|---|---|

| 10-Year Treasury | 4.5% | 2.7% |

| Municipal Bond | 3.8% | 3.8% |

| Private Credit Fund | 10.0% | 6.0% |

| Real Estate (w/depreciation)* | 7.0% | 5.5%+ |

*Real estate after-tax yield varies significantly based on depreciation, leverage, and holding period.

The tax efficiency of real assets often widens the gap between traditional bonds and alternatives far beyond what headline yields suggest.

Private Credit for Founders

Private credit used to require institutional scale. Minimum investments of $1 million or more, lengthy lockups, and accredited investor requirements put it out of reach for most.

That's changed. Retail investors now account for roughly 13% of private credit assets under management—up from virtually zero a decade ago, according to Bank for International Settlements research. Several structures make access possible:

Publicly Traded BDCs (Business Development Companies)

BDCs are closed-end funds that lend to middle-market companies and trade on public exchanges like stocks. They offer daily liquidity, SEC oversight, and yields typically in the 8-12% range. The trade-off: share prices can be volatile and may trade at discounts to net asset value during market stress.

Major publicly traded BDCs include Ares Capital (ARCC), Blue Owl Capital Corporation (OBDC), and Main Street Capital (MAIN). Combined, publicly traded BDCs manage over $140 billion in assets.

Non-Traded BDCs

These offer similar exposure without the daily price volatility of public markets. Shares are priced at net asset value rather than market sentiment. Liquidity is more limited—typically, quarterly redemption windows that can be suspended during stress. Blackstone's BCRED is the largest, having gathered $6.4 billion in inflows in 2024 alone.

Minimum investments vary but often range from $2,500 to $25,000, depending on the platform and share class.

Interval Funds

A newer structure that combines private credit exposure with periodic liquidity, typically offering to repurchase 5% of shares quarterly. Interval funds provide more liquidity than traditional private credit funds while avoiding the market-price volatility of traded BDCs. Yields generally target 7-10% annually.

Cliffwater and StepStone manage some of the largest interval funds focused on private credit.

Key Considerations

Fees matter significantly in this space. Management fees of 1-2% plus incentive fees of 15-20% of profits are common. Those costs compound. Before committing, founders should understand the all-in expense ratio and whether the manager's track record justifies the premium.

These vehicles issue 1099s rather than K-1s, simplifying tax filing compared to traditional private partnerships—a meaningful convenience factor for busy founders.

Yale Model's Lasting Influence

The shift toward alternatives has roots deeper than the 2022 bond rout. David Swensen pioneered this approach at Yale's endowment starting in 1985.

When Swensen took over, Yale's portfolio looked like everyone else's: heavily weighted toward domestic stocks and bonds, resembling a typical mutual fund. He transformed it into something radically different, emphasising private equity, venture capital, hedge funds, and real assets while minimising traditional fixed income.

The results were extraordinary. Over his 36-year tenure, Swensen grew Yale's endowment from $1.3 billion to over $40 billion, achieving a 13.7% annualised return that outperformed the average endowment by 3.4 percentage points.

Swensen's insight was recognising that liquidity comes at a cost. Traditional portfolios prize the ability to sell quickly. But investors with long-term horizons don't need daily liquidity. They can earn what he called an "illiquidity premium" by accepting capital lockups in exchange for higher expected returns.

By 2019, roughly 60% of Yale's portfolio sat in alternative investments. Domestic stocks and bonds fell from nearly three-quarters of the endowment in 1989 to less than a tenth by the early 2020s.

Other endowments followed. So did family offices. The UBS report confirms that American family offices now align more closely with Yale's approach than traditional retail portfolios. The strategy works best for investors who don't need quick access to capital, can evaluate complex investments (or hire advisors who can), and have the scale to access institutional opportunities.

Geographic Diversification

Most allocation discussions focus on asset class diversification while ignoring geography entirely. For globally mobile founders, that's a significant oversight.

Political risk is real. Regulatory changes, tax policy shifts, currency movements, and even asset seizures can devastate concentrated portfolios. Investors who lived through emerging-market crises—or who watched Russian assets frozen in 2022—understand this viscerally.

Family offices increasingly structure holdings across multiple jurisdictions:

- Operating companies in business-friendly domiciles (Delaware, Singapore, Dubai)

- Investment holding companies in jurisdictions with favourable tax treaties and asset protection

- Real estate diversified across stable markets rather than being concentrated in a single city

- Banking relationships across multiple countries and currency zones

- Citizenship and residency provide optionality for where to live and work

This isn't about aggressive tax optimisation. It's about building resilience against country-specific risks that no single jurisdiction can eliminate.

A founder with $10 million concentrated entirely in US assets faces different risks than one with $4 million in US equities, $2 million in European real estate, $2 million in Singapore-based private credit, and $2 million in portable liquid assets. The latter sleeps better during election cycles, regulatory shifts, or geopolitical tensions.

For founders who built global businesses, extending that global mindset to personal wealth just makes sense.

3 Ways This Goes Wrong

Even smart, wealthy investors make mistakes with alternative-heavy portfolios.

Concentration Risk

The Archegos collapse in March 2021 illustrates what happens when concentration goes too far. Bill Hwang ran his family office into positions worth over $50 billion using just $10 billion in capital—leverage of 5:1 concentrated in a handful of stocks.

When ViacomCBS announced a surprise share offering, the cascading liquidation wiped out Hwang's $20 billion net worth in roughly 48 hours. Banks lost over $10 billion combined. Hwang was sentenced to 18 years in prison for fraud related to the scheme.

Diversification within private markets matters as much as diversification across them.

Fee Layering

Private investments carry higher costs than index funds. A typical private equity fund charges 2% management fees plus 20% of profits above a hurdle rate. Fund-of-funds add another layer. Some investors end up paying 3-4% annually before any performance sharing.

Those fees compound against returns relentlessly. A 15% gross return becomes 10% or less after costs.

Fake Diversification

Owning 50 different investments provides no protection if they all respond to the same factors. A portfolio stuffed with leveraged private equity, high-LTV real estate, and private credit to levered borrowers isn't diversified—it's a concentrated bet on low interest rates and easy credit conditions.

True diversification means owning assets that behave differently under different scenarios.

Questions to Ask

Before restructuring a portfolio, these questions help separate genuine expertise from product-pushing:

About Alternatives Access:

- What is the all-in fee (management, incentive, fund expenses) for each alternative investment?

- How does liquidity actually work—and what happens during market stress?

- What is your track record of selecting managers in this space?

About Concentration:

- What percentage of my portfolio is exposed to the same underlying risk factors?

- How does this allocation perform in a rising rate environment? A recession? A stagflation scenario?

- What's the maximum I should have in any single manager or strategy?

About Tax Efficiency:

- Have we modelled the after-tax returns, not just pre-tax?

- Are we using the right account types (taxable vs. tax-advantaged) for each investment?

- What's the estate planning impact of these structures?

About Suitability:

- Is this allocation appropriate for my actual liquidity needs over the next decade?

- How much of this is driven by my situation versus your firm's product availability?

- What would you change if fees weren't a factor?

Advisors who bristle at these questions or can't provide clear answers are telling founders something important about the relationship.

How to Think About Asset Allocation

No single allocation works for everyone. A 35-year-old founder who just sold a company should invest differently than a 65-year-old focused on income and legacy planning.

Several questions help frame the decision:

How much needs to stay liquid? If capital must be accessible for business opportunities, real estate purchases, or personal needs, that money can't sit in 10-year private equity lockups.

What's the actual time horizon? Someone investing for grandchildren has fundamentally different constraints than someone funding their own retirement.

Where does genuine edge exist? A software founder understands SaaS businesses and can evaluate enterprise software deals with sophistication. That same person might have no edge evaluating biotech development or energy infrastructure.

What level of involvement makes sense? Some investors want to evaluate every deal and serve on boards. Others prefer to select managers and let them operate.

A simple framework: keep 60-70% in core, liquid holdings that can weather storms and provide flexibility. Use the remaining 30-40% for opportunistic investments in private markets where genuine illiquidity premiums exist. Adjust the ratio based on liquidity needs and time horizon.

What This Means

The 60/40 portfolio served its era well. But that era has passed.

The conditions that made it work—reliably negative stock-bond correlations, meaningful bond yields, limited access to alternatives—have all shifted. Wealthy investors recognised this years ago and rebuilt their portfolios accordingly.

This doesn't mean everyone should dump their bonds tomorrow and pile into private equity. Access matters. Knowledge matters. Time horizon matters. Most individual investors lack the scale, expertise, and patience to implement these strategies effectively.

But for founders and entrepreneurs managing significant capital with multi-decade horizons, the evidence is clear: clinging to the old allocation model means accepting lower expected returns without the diversification benefits that justified the trade-off in the first place.

The transition doesn't need to happen overnight. Start by understanding what drives returns in private markets. Build relationships with managers who have genuine track records. Evaluate whether specific opportunities fit your knowledge base and liquidity constraints. Move capital gradually as comfort and access increase.

Family offices aren't following some secret playbook. They're responding rationally to changed conditions—allocating where the risk-adjusted returns justify the complexity and illiquidity. The question for other investors is whether to keep waiting for the old model to work again—or to acknowledge that the game has changed and adapt accordingly.

The founders who built their wealth through concentrated bets on businesses they understood deeply don't suddenly need to pretend they can't evaluate private investments. The same analytical rigour that created the wealth can be applied to preserving and growing it—just in a different context.

That's the real lesson from how family offices invest. It's not about access to exotic products. It's about thinking like an owner rather than a passive participant in someone else's index fund.

I write when there’s something worth sharing — playbooks, signals, and patterns I’m seeing among founders building, exiting, and managing real capital.

If that’s useful, you can subscribe here.