I remember February 2014 with uncomfortable clarity.

In just a few days, I watched millions vanish—my millions, at least on paper. Not gradually, as most people do when they lose money. All at once.

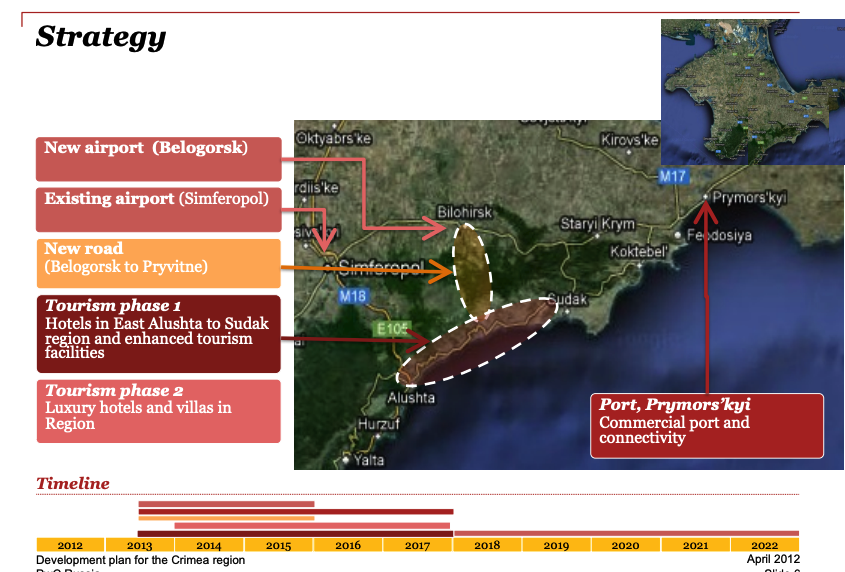

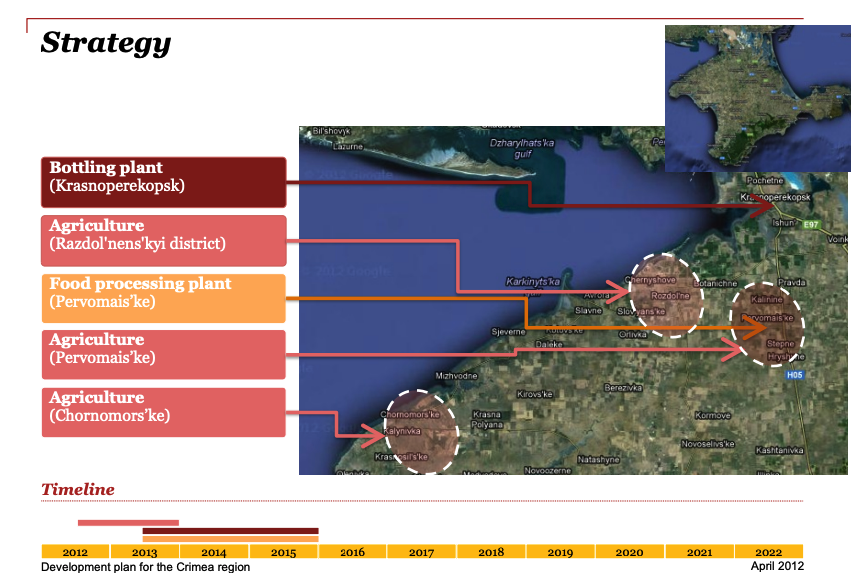

Just months earlier, we had returned to London from China carrying a signed term sheet for over $200m. Four years of work had gone into assembling a billion-dollar infrastructure deal in Crimea: a new airport, deep-water seaport redevelopment, road reconstruction, residential real estate, and agricultural projects. The deal brought together the Crimean government, Chinese state-owned enterprises, major construction companies, global banks, and UK corporates. My partners and I had invested ourselves heavily.

What many thought impossible was finally coming together. We were months away from breaking ground.

Then, the peaceful protests in Kyiv turned violent. Hundreds of people died. We told ourselves things would cool down, that we'd face delays, but that was wishful thinking.

Then Russia annexed Crimea.

Our government counterparts were gone. The legal framework we'd built everything on became irrelevant. International sanctions made any Crimea-related project untouchable. The Chinese partners walked away. I couldn't blame them.

Four years of work. Significant personal investment. Gone in a day.

I spent a long time afterwards trying to make sense of what had happened. Months, probably. What I should have seen. What I was supposed to do next.

I didn't find the answers I was looking for. But eventually, I discovered some useful questions.

That's what this story is really about.

Where the Instinct Comes From

I was born in Ukraine in the early 80s, back when it was still the Soviet Union. My childhood was normal enough—middle-class parents, school, sports, friends.

I don't remember much about daily life under the Soviet system since I was just a kid, but a few moments stand out clearly.

In the late 1980s, as the Soviet Union was falling apart, borders remained closed for most people. Store shelves sat empty. Long queues everywhere. Many families had money. They just couldn't spend it—there was nothing to buy.

Then, when the Soviet Union collapsed, millions of people lost their life savings overnight. I remember my parents talking about my grandfather (who was in his early 50s when he passed away). He had worked hard his entire life and had enough to buy an apartment, maybe two. But you couldn't buy property back then—it wasn't allowed. Then overnight, his savings became worthless. So did everyone else's.

Meanwhile, the few who were smart or lucky enough to buy real assets during the short window when it was possible changed their lives forever.

There was another moment I remember more clearly, because I was older. In the late 1990s, around the time of the Russian default, Ukraine experienced hyperinflation. My father was running a business then. He had borrowed money from the bank and bought a new car. Within about a year, inflation had climbed so high that the amount he originally borrowed was roughly equivalent to my pocket money for school. He paid off the loan easily.

At the time, I thought he was clever and lucky. Later, I realised this was how both big and small oligarchs made their fortunes then. Those with access to capital borrowed heavily, bought assets like factories, refineries, and land, and watched inflation wipe out their debts.

But it wasn't just about being smart—it was about having the right connections. These were tough times. People were killed over business disputes, and organised crime controlled everything. When people talk about the Russian mafia, it's this period, "wild nineties" as we called them. I grew up in the middle of it.

The difference between those who thrived and those who didn't wasn't intelligence, I don't think. It was adaptability. When the Soviet Union fell, many capable people were left with nothing because they couldn't adjust to the new reality.

Learning to Fight

I started boxing at fourteen. It was the skill you needed to survive on the streets—and make useful connections.

My town had just two real boxing gyms, so I started in a makeshift setup in a student housing basement. There were some weights, a few bags with sand, and an older friend who taught me the basic techniques. When I moved to a proper gym, I joined the "amateur" class first, where people came to try it out. I trained obsessively, and soon I was invited to the "professional" group, where guys trained to compete.

That became my life for over six years. Training almost every day. In preparation for tournaments, twice a day. I won regional competitions. Went to nationals. I made good friends that I still have.

I also had a couple of show fights in London in semi-pro

I also spent two years competing in hand-to-hand combat (which was practised in the military and special forces). Back then, there was no MMA, but this was close. Almost all strikes allowed, minimal rules. If you went to the ground, you either got a submission quickly or stood up and kept fighting.

But sport wasn't a career path, especially then. There was no money in it. After university, a couple of injuries made serious training impossible, and it was time to figure out how to earn a living.

The lesson was obvious, even if it took me years to really get it: life throws punches constantly. Most people are afraid to step into the ring—they spend their lives watching from the sidelines. Yes, getting hit in the face is scary the first time. It hurts. But you keep showing up. You grind. With discipline and persistence, you get better. You start winning. You improve by fighting bigger, better opponents. There's no other way.

The Streets of London

I arrived in London in 2004 with a few hundred dollars and a job at a countryside hotel—the only way to get a visa at the time. I thought I'd stay a year, then return home.

That's not what happened.

The hotel job wasn't for me. After a couple of months, I packed my things and moved to London, where I knew just one person. I asked to stay at their place for a few days while I figured things out.

That's where I met my future wife. She was renting a room in the same house. Shortly after, I moved in with her, and we've been together for nearly twenty years now.

My first real job in London was commission-only field sales. You remember those shopping centre stands where people sign you up for broadband? That was me.

The company paid minimum wage for two weeks of training. After that, you were on your own—it was sink or swim. You'd be part of a team, similar to a multi-level marketing model. There was a team leader, someone on the team who was more experienced to look after you, and if you did well, you could eventually build your own team.

It was the most challenging work I've ever done. My English was rough. I had an accent. Convincing strangers to sign up for a direct debit on the spot was not easy. Some days I did alright. Some days I made nothing.

For six or seven months, I worked two jobs. Sales during the day. Pub shifts in the evenings and weekends.

I'd wake at 6am to reach some distant shopping centre outside London by 8am. Home by 4pm. At the pub by 6pm. Home around midnight. On weekends, I'd start at the pub at noon and work until late into the evening.

But here's what I learned: how to handle rejection without falling apart; how to approach strangers and start conversations; the importance of following a system; and how to stay motivated even when everything tells you to quit.

I talked to hundreds of people every day. Many told me to fuck off.

Those skills turned out to be more useful than anything I learned in university. Same lesson as boxing, really—just translated to business. Keep grinding. Deal with rejection. Develop thick skin. Sales (in a broader sense) is one of the most critical life skills, and most people never learn it because they're afraid to hear "no."

Into the City

From field sales, I moved into recruitment. Then executive search.

While doing field sales, I wanted an office job, but that wasn't easy without a UK degree. My Ukrainian economics degree meant little here.

I found a part-time gig—two days of work for a group of companies doing recruitment, accounting, and IT services. They were launching a new service and preparing for a trade show at ExCeL. The job was simple: talk to visitors, collect their contact details for follow-up.

Walking up to strangers and getting their name and number without setting up a direct debit on the spot? Easy.

At the end of the second day, I had signed up more leads than the other fifteen people combined.

The next day, I was offered a full-time position. A year later, I was recruited to a proper headhunting firm in the City.

Executive search is a different world. You're placing VPs, MDs, and C-suite executives at investment banks, hedge funds, and private equity shops. People running billion-dollar deals.

I spoke Russian and Ukrainian, so I specialised in emerging markets, including Russia and the CIS. These were growth markets in the mid-2000s. Western banks were expanding quickly and paying premium rates to people willing to relocate. The same job in Moscow could pay several times as much as in London or New York.

My first placement—moving someone from London to Moscow—earned the firm around £50,000. My previous recruitment job averaged £5-7k per placement at best. Soon after, I placed someone from New York in Moscow. That fee was around £150,000.

Over the next two years, I placed everyone from VPs to global heads and CEOs. London, New York, Moscow, Kyiv. Built relationships with prominent names in finance. Travelled extensively. Started thinking about starting my own firm.

Then Lehman Brothers collapsed. September 2008. I remember exactly where I was when I heard the news.

Suddenly, nobody in investment banking was hiring. Despite being a top performer at my firm, I was let go.

So I started my own company. Picked up a couple of mandates to pay the bills and get me through the challenging times. But I also realised that the industry was changing and recruitment would never be as lucrative or interesting as before.

I knew this wasn't my long-term path. I didn't want to spend my life facilitating other people's careers. I wanted to build something. Create real value. Have skin in the game.

That experience taught me something I think about often: you can be employee of the year, top performer in your firm, and still get let go for reasons that might have nothing to do with you. Unfair? Possibly. But that's how things work. Understanding this is the first step toward taking control of your life. Treat your career like a business you own, not a job you have.

The Big Bet

In 2011, I met two guys who would become my business partners in the biggest undertaking of my life.

One of them I knew from boxing. We'd sparred together for years at a gym in London. He knew about my connections in Russia and the CIS region.

One day, he approached me about business.

He and his partner had just secured backing from a UK FTSE-listed company's subsidiary to fund their new venture. They had strong relationships with China's state-owned enterprises and banks. The mandate: source infrastructure projects globally that Chinese institutions could finance and build, with their UK backer overseeing everything.

Could I look at Russia and Ukraine to originate projects?

A few months later, as it happened, Crimea's government was on a roadshow in London, seeking investment. A delegation led by the Prime Minister was visiting. We attended. There was a "shopping list" of projects: airport construction, industrial seaport development, roads, a yacht marina, real estate, you name it.

After the presentations, I walked up to the Prime Minister, introduced myself briefly, and said we were interested in talking. He called over the person leading their investment efforts. We exchanged cards. A few weeks later, we were on our way to Crimea.

What started as a favour to friends became the next five years of my life.

After that first visit, they asked me to join as an equal partner. Over the next few years, we assembled a public-private partnership worth over $1bn.

The structure made sense. Commercial projects—real estate development and agricultural operations—would generate returns to fund public infrastructure: the airport, seaport, and roads. Chinese debt funding would cover construction. The Crimean government would provide land, permits, and political support. We would manage it all.

We also secured equity investment to cover the project's risk capital.

The negotiations were endless. Flying between London, Beijing, and Simferopol. I still remember those 5-hour layovers in Dubai or Istanbul. Formal meetings that would go into long lunches or dinners, with hours of toasts before anyone discussed business. It was challenging but also great fun.

Crimea Goverment Delegation visits to China

We weren't just advisors; we were operators. We held significant equity in the holding company and had real skin in the game.

We spent considerable time in both Ukraine and China, hosted senior government visits in both countries, and built relationships at every level.

We signed a term sheet with a Chinese bank for about $200m to finance the first phase.

A few months later, we lost everything.

The Aftermath

You already know what happened. What I haven't told you is what came after.

With Crimea under Russian control, our entire effort went to zero. Given our focus on Russia and Ukraine, and the sanctions that followed, both markets were effectively closed to us. Ukraine was at war. Russia was under sanctions.

We had invested heavily—our own money, some of it borrowed. We lost everything.

We had borrowed from people who believed in us. Technically, it was business funding that could be written off. But we gave our word to repay everyone who had supported us. And we did.

So I started over. Not from zero, but from several floors below zero.

All the connections I'd built in Russia and the CIS—the market I knew best—were suddenly irrelevant. The geopolitical landscape had shifted.

I had to reinvent myself. Again.

Here's what that taught me: always keep tail risk in mind—the kind of event that has never happened before but could be just around the corner. Hope for the best, prepare for the worst. Try to think a few steps ahead—what could go wrong? Hedge your bets. Diversify.

We hear stories about entrepreneurs who made bold, concentrated bets and made fortunes. Yes, those people exist, but the odds are maybe 0.1%, probably less. For every one of them, hundreds of thousands lost everything with the same approach. Those aren't the stories anyone tells.

Rebuilding

In 2016, while figuring out what to do next, I reconnected with someone who would become my current business partner. We had worked together before, helping a large Chinese institutional investor set up a fund to invest in UK real estate.

They were launching a new venture. There was no headcount yet, but I was interested. While working on consulting projects elsewhere, I spent all my free time helping get this project off the ground.

Those few months turned into a full-time role. The role turned into a partnership. The partnership turned into equity.

The business was going through its own transformation. It had started as a hedge fund and investment adviser, but the industry was changing. They were also transforming the business, and I joined at the earliest stage of that new chapter.

This group wasn't trying to build one thing. They were building wealth infrastructure. Acquiring independent wealth management firms and making them better. Creating a digital-first advice & investment platform to scale. Thinking systematically about an industry ripe for consolidation.

Today, we oversee around £2 billion in client assets. We've acquired multiple firms. We built the first-of-its-kind digital advice platform in the UK (think Shopify for financial advisers) that lets them run their entire practice online. We provide investment management services ranging from low-cost model portfolios to alternative and absolute return strategies.

We keep growing organically and through acquisitions. We have an excellent team. We build things that make a real difference.

I've realised there's more than one way to build. The big, dramatic bet is one approach. Patiently accumulating assets and capabilities is another. The second path may seem slower—and maybe less exciting—but it's far more resilient.

I'm not sure I would have understood that before Crimea. Losing taught me to value durability over speed.

Why Capital Founders OS Exists

The idea came to me some time ago. 2026 is when I'm bringing it to life.

This is a side project, but I've been thinking about it for a while. More importantly, I operate at an unusual intersection:

I've spent years building businesses as a co-founder and entrepreneur. I also work in the investment and wealth management industry. While I don't provide financial advice to end clients directly, I've helped many UHNW individuals and contacts solve complex problems.

If there's one thing my path taught me, it's that very little is actually impossible. What matters is how you think, the systems you build, and whether you'll do the work.

Over the past several years, I've worked with and crossed paths with many business owners and entrepreneurs—people worth hundreds of millions of dollars. I've helped solve problems that seemed impossible. I've seen a lot.

And I see the challenges people like us face.

I know people who made serious money, and then lost millions by approaching investing the way they approached business. Psychological biases. Overconfidence. Not understanding how capital markets actually work.

There's also a group I call emerging wealthy founders—too big for typical retail solutions, but too small for institutional setups. Managing capital takes a different skill set than building a business, and it's essential to recognise that difference.

If you're reading this, you probably know the type. Maybe you are the type. $5 million to $50 million in assets. Running a business worth eight figures or approaching an exit. High-agency, self-made, internationally minded. Operating in digital, tech, or emerging industries. Sceptical of mainstream advice. Wanting to understand how things actually work.

Traditional financial advice and wealth management aren't built for people like us. Builders. Operators. Risk-takers.

I'm writing this content for myself as much as for anyone else. It helps me systematise my thinking, make notes, learn in public. And that is kind of the next skill I want to develop.

I see it as an operating system for Capital Founders OS: a framework for building and protecting wealth, navigating uncertainty, and becoming financially unbreakable.

I also want to build a community of like-minded people who are on the same journey. So we can share ideas and learn from each other.

What I'm Still Learning

I want to be clear: I don't have everything figured out.

I'm still learning. Still making mistakes. Still discovering things I thought I understood but didn't.

A few things I'm actively working through:

I'm an entrepreneur at heart. I want to build, take risks, and make bets. But I've learned what happens when you're too concentrated and don't protect the downside. Finding the right balance between building and preserving remains an ongoing challenge.

Thinking about risks is another. After Crimea, I became much more aware of political and jurisdictional risk. But I'm still learning how to incorporate that into actual decisions. How much weight to give it? When to act on it versus accept it. This is hard. I don't think anyone has great answers.

Helping without prescribing matters to me. In writing this, I'm trying to educate without telling people what to do. Respecting their intelligence while sharing what I've learned. That balance is something I'm still figuring out.

Building in public. Sharing my story publicly is new for me. I'm still learning what to share and what to keep private. Where the line sits between authenticity and oversharing.

Pretending to have all the answers would not be true. I don't. I'm a few steps ahead on some things, a few steps behind on others.

What I can offer is my perspective. What I've seen and learned the hard way.

A Few Other Things About Me

Some additional context that might help you understand how I see the world:

I approach life with a player's mentality, not a spectator's. We each choose our path. Everyone has their own journey—some harsh, some easier. But each of us faces challenges we must overcome to advance. Most people watch from the sidelines. I prefer to stay in the game.

I'm interested in what's ahead: entrepreneurship, emerging technology, AI, the digital economy, new business models and opportunities.

I think a lot about life design: mental systems and frameworks, personal productivity, peak performance, longevity, and wellbeing.

And I remain deeply curious about how things actually work—beneath the surface narratives we're given.

What Comes Next

That's the story. Or at least the version I can tell in a few thousand words.

You know I came from nothing and built something meaningful. You know I lost it and rebuilt. You know I'm still building, learning, and trying to understand how the world really works.

Capital Founders OS is where I share that journey. Not as someone who has arrived, but as someone still on the road. Further along than some. Not as far as others.

If you want to come along, subscribe to the newsletter. I share my best thinking regularly. No spam. No pitches. Just what I'm learning about building and protecting wealth as a founder.

If you landed here first and want to understand what Capital Founders OS is about, read the About page.

And if anything in this story resonated—if you've been through something similar, if you're facing decisions I might understand—reach out. I read everything.

The game continues.

— Taras