Chapter 2 of Running a Family Office Under $100M

The traditional family office playbook is simple: hire a team of dedicated staff to manage everything.

There's just one problem. That approach doesn't make economic sense until you're well above $100 million. A full single family office—CIO, CFO, administrative support, office space—runs $1-2 million annually before you've made a single investment. At $20 million in assets, that's 5-10% of your wealth just in overhead.

So what do you do if you're at $15 million? Or $40 million? Too complex for DIY, too small for the traditional model.

You need a different approach. Three models have emerged for founders in the $5–100M range, and choosing the wrong one either costs you money or costs you time. Often both.

Key Takeaways

- Traditional family offices require $100M+ to justify the cost—below that, you need a different model

- Model A: Coordinated Advisor Network ($5–15M)—You quarterback independent specialists; costs 0.5–0.8% annually; requires 5–10 hours/month of your time

- Model B: Virtual Family Office ($15–50M)—Outsourced coordination layer manages your advisors; costs 0.6–1.25% annually; requires 2–5 hours/month

- Model C: Lean Single Family Office ($50–100M)—One dedicated hire plus external specialists; costs 0.75–1.5% annually; requires 2–4 hours/month

- Most founders should start with Model A and graduate to Model B when coordination becomes burdensome

- The key word is "coordinated"—having advisors who never talk to each other isn't a network, it's a collection of silos

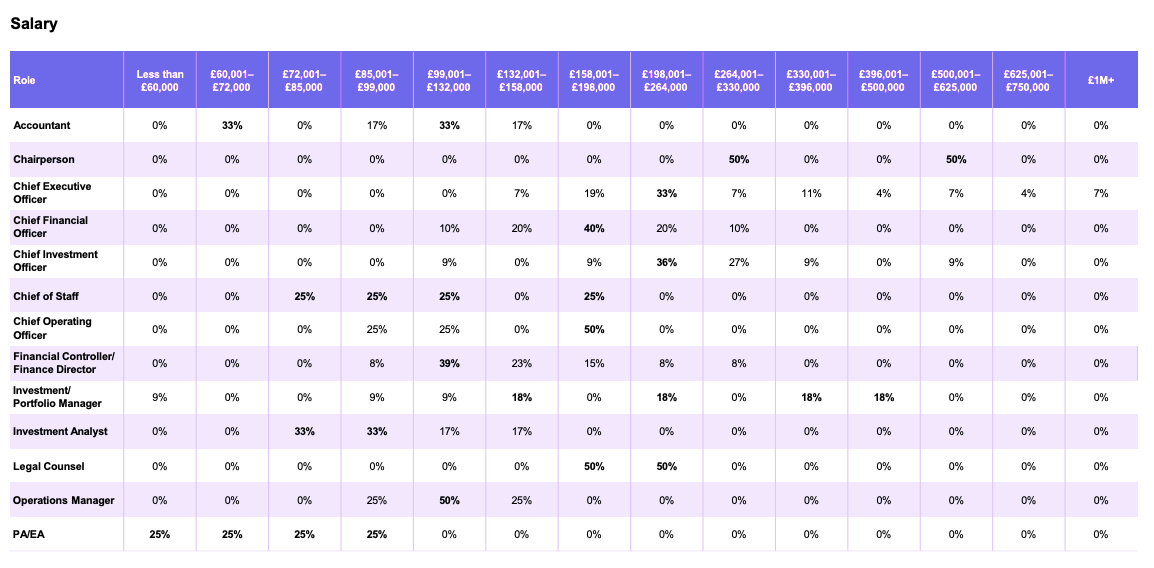

The KPMG/Agreus 2025 Global Family Office Compensation Benchmark Report puts UK family office CEO salaries most commonly at £198,000–£264,000. In the US, that jumps to $396,000–$500,000. Add a CIO (median compensation around $337,000 at smaller offices, according to Campden Wealth), support staff, office costs, and technology—you're easily north of a million annually.

Model A: Coordinated Advisor Network

This is where most founders start. And honestly, where many should stay until their situation genuinely demands more.

The idea is simple. You assemble independent specialists—tax advisor, estate attorney, investment platform, insurance broker—and you coordinate them yourself. You're the quarterback. You make sure they talk to each other, share information, and don't work at cross purposes.

Notice I said "coordinate them yourself." That's the catch. Having advisors isn't the same as having a coordinated team. I've met plenty of founders with four or five advisors who've never been in the same room together. Never even spoken. Each one doing their thing in isolation. That's not a network. That's just... people you pay.

For this to work, you need to be deliberate about it. Introduce your advisors to each other. Actually make the introduction—"This is my tax advisor, this is my estate attorney, here's each other's contact info." Schedule a call once a year where your tax and investment people are both on the line. You'd be surprised what they catch when they actually talk.

The costs are reasonable. Tax work runs $5,000–$15,000 a year depending on complexity. Estate attorney maybe $5,000–$10,000 for setup, then a few thousand annually for reviews. Investment platform or advisor charges 0.15–0.50% on assets. Insurance broker usually works on commission. All in, you're looking at 0.5–0.8% of assets. On $10M, that's $50,000–$80,000 per year.

The time cost is the real question. Figure 5–10 hours a month for coordination, reviews, keeping everything moving. If that feels fine given your schedule and what your time is worth, this model works great.

But there are risks.

The obvious one is that coordination doesn't happen unless you make it happen. Advisors are busy. They have lots of clients. Unless you force the interaction, they'll stay in their lanes and miss things that fall between the gaps.

The less obvious risk is that you become a bottleneck. Every decision waits for you. You go on holiday for three weeks, nothing moves. You get busy with a new project, things pile up. And some advisors—not all, but some—will just wait passively for you to ask the right questions rather than proactively flagging issues. If nobody's looking for problems, problems accumulate quietly.

When does it stop working? When you're spending more time on this than you want to. When things start slipping through cracks. When complexity grows beyond what you can reasonably track—more entities, more jurisdictions, more alternative investments with their own reporting requirements.

That's when you start looking at Model B.

QUICK ASK — Everything here is free. If you're finding this useful, subscribing helps me understand what's working — and keeps you updated when new pieces come out.

Model B: Virtual Family Office (VFO)

The VFO adds a coordination layer. Instead of you being the quarterback, someone else does that job. You focus on the decisions that actually need your input.

A VFO provider oversees all your advisor relationships, pulls together consolidated reporting, flags issues before they become problems, and serves as your first call when something financial comes up. You still have the underlying specialists doing the actual work. But someone else makes sure they're working together.

There are different types. Multi-family offices serve multiple families with shared infrastructure—could be a small boutique with 10 families or a large firm with hundreds. Boutique wealth advisors offer similar services, often started by people who left the big banks and wanted to do things differently. And there are independent coordinators—individuals, usually former private bankers or family office people, who'll quarterback your team on a retainer.

Finding a good one takes some work. Start with referrals from advisors you already trust. Your tax accountant or estate attorney probably works with VFOs and knows which ones actually deliver. Founder networks are another source. Industry associations like Family Office Exchange, Simple or Spear's 500 maintain directories. Expect to talk to 3–5 before you find the right fit.

When you're evaluating them, a few things matter more than others.

Independence is the big one. Do they sell products and earn commissions, or are they paid only by you? Those are different incentive structures, and they lead to different advice. A VFO that earns money when you buy their affiliated funds will tend to recommend their affiliated funds. Not always consciously. But the bias is there.

Client ratio matters too. How many families per advisor? Below 20 is decent. Above 50 means you're not getting real attention—you're getting a relationship manager who's stretched too thin.

And watch out for the bait-and-switch. You meet with senior partners during the pitch. They're impressive, thoughtful, clearly experienced. Then you sign up and get handed to someone three years out of university. Ask upfront who your actual day-to-day contact will be. Meet them before you commit.

The cost runs 0.5–1.25% of assets annually. The UBS Global Family Office Report 2024 puts MFO fees in the 0.2–1.25% range, with most full-service arrangements landing at 0.5–1.0% for investment management plus retainers between $25,000 and $250,000 annually for additional services.

On $25M, that's roughly $125,000–$310,000 per year. Sounds like a lot. But it typically includes coordination, reporting, investment management, and access to opportunities you wouldn't get otherwise. Compare it to what you'd pay for all those things separately, plus the value of your time.

There's also an unwritten rule in the industry: the "100k threshold" MFOs generally want at least $100,000 in annual revenue from each client to make the relationship worthwhile. Below that, you're likely to get less attention—or politely declined. For a $10M portfolio paying 1%, you're at that threshold. For $5M, you may need to negotiate hard or accept limited service.

Time commitment drops to 2–5 hours a month. Quarterly reviews, occasional decisions, that's about it.

Model C: Lean Single Family Office

At some point, shared infrastructure isn't enough. Your situation needs dedicated attention. But you're not at the scale where a full family office—multiple staff, office space, all the overhead—makes economic sense.

The solution is one key hire. Call them a family office director, a Chief of Staff for Wealth, whatever title works. One senior person whose only job is managing your financial life.

They coordinate all the external advisors. They handle reporting and administration. They manage entities, compliance, filings. They evaluate opportunities and bring you the ones worth your time. They're your single point of contact for everything financial.

The specialists still do the specialist work—tax planning, legal documents, investment management. But you have someone dedicated to making sure the whole system runs.

This hire is the linchpin. Get it right and everything works smoothly. Get it wrong and you've just added an expensive problem.

You want someone who can work across domains—tax, investments, legal, admin—without being a deep specialist in any of them. Previous family office experience helps. Private banking background works. They need to be technically strong enough to evaluate what the specialists are telling you. Organised. Proactive. And trustworthy, because they'll have access to everything.

Compensation runs £150,000–£300,000+ in the UK. The KPMG/Agreus 2025 report shows UK family office CEOs most commonly earning £198,000–£264,000, with significant variation based on complexity and location. London commands a premium. For a capable but not C-suite level director, £150,000–£200,000 is realistic. Below £150K, you're probably not getting someone experienced enough.

Where do you find them? Private banks and multi-family offices are the usual hunting grounds—people who've served wealthy clients and want to work with one family instead of many. Executive recruiters specialising in family offices exist (Agreus Group, Botoff Consulting, a few others). If you're transitioning from Model B, your VFO might have candidates or be willing to help place someone.

Expect a 3–6 month search. This isn't a hire you rush.

Here's the cautionary note. I've seen founders jump straight to this because it felt like the sophisticated thing to do. One went "institutional-grade" when he decided to start playing the "investing game"—prime brokerage accounts, expensive staff, infrastructure designed for $200M+.

Then reality set in.

Prime brokerage accounts have a minimum of $500,000, but to get any meaningful services or discounts, you typically need $50 million or more. They're designed for hedge funds running complex strategies with borrowed securities—not for individual investors managing a diversified portfolio. He wasn't trading enough to justify the fees or generate the activity the platform expected.

The principal didn't have enough complexity to manage. He ended up paying high fees for services he didn't use, and his investment adviser couldn’t utilise this infrastructure.

Model C makes sense when complexity genuinely demands dedicated attention. Not as a status symbol. Not because your friends have one.

The numbers: 0.75–1.5% of assets all-in, including the hire and external specialists. On $75M, that's £560K–£1.1M annually. Time commitment drops to 2–4 hours a month plus quarterly strategic sessions.

The key risk is concentration. Your whole system depends on one person. What if they leave? Get sick? Underperform? You need documentation, backup plans, and succession thinking from day one.

So Which One?

Simple situation—single country, mostly public markets, straightforward family? Model A is probably fine.

Moderate complexity—multiple entities, some alternatives, maybe some international elements? Could be Model A with good systems, could be time for Model B.

High complexity—multiple jurisdictions, significant alternatives, active businesses, complex family dynamics? Model B or C.

Beyond complexity, think about your time. Model A takes 5–10 hours a month. If you have that time and don't mind the work, great. If you'd rather spend those hours elsewhere (and get better returns on your time), pay someone else to coordinate.

And think about trajectory. If your situation is stable, optimise for now. If complexity is growing—another exit coming, international move, next generation getting involved—build infrastructure slightly ahead of need. Catching up is harder than staying ahead.

You can also check our Family Office Location Guide.

Patterns I Keep Seeing

The reluctant DIY-er. Running Model A because they haven't found a VFO they trust. Spending way more time than they admit, stressed about things falling through cracks. Should either get serious about making Model A work or find the right partner.

The over-built. $12M in assets, paying $150K+ for services designed for $50M+. Feels sophisticated but the economics are upside down. The Campden Wealth European Family Office Report 2024 is instructive here: family offices with less than $500M in AUM average costs of 105 basis points—nearly three times higher than those managing over $1 billion (36 basis points). Scale matters. If you don't have it, don't pretend you do. Should simplify to Model A and revisit when wealth grows.

The under-built. $40M, three jurisdictions, growing alternatives portfolio, still running the same Model A setup from when they had $5M. Things are slipping. Tax surprises. Missed opportunities. Should have moved to Model B a while ago.

The premature hire. Brought on a family office director at $30M because it seemed like the thing to do. Now has an expensive employee without enough to do. VFO would have been the right call. Hard to unwind gracefully.

Moving Between Models

Transitions take time.

Going from A to B means introducing the VFO to your existing advisors. Some might feel displaced. The VFO might identify underperformers you've been tolerating. Give it 3–6 months to settle.

Going from B to C is a bigger shift. You might keep the VFO during transition for continuity. Your new hire should meet all existing advisors before they start. Plan for a 6–12 month ramp-up.

Stepping back—C to B, or B to A—happens too. Wealth decreases, complexity simplifies, economics change. Do it carefully. Don't burn bridges. You might need to scale back up later.

Questions to Ask Yourself

- How many hours a month do you actually spend coordinating your financial life? Not how many you think you should spend—how many you actually spend. Is that sustainable?

- When something falls through the cracks—missed filing, overlooked opportunity, conflicting advice—how does it get caught? Or does it just not get caught?

- If your complexity doubled in two years (another exit, international move, more alternatives), would your current setup handle it?

- Are you the bottleneck? If you disappeared for a month, would everything keep running?

The goal isn't the most sophisticated model. It's the right model for where you actually are—one that can evolve as things change.

← Back to Chapter 1: What a Family Office Actually Does

Continue to Chapter 3: Structure — The Foundation →

I write when there’s something worth sharing — playbooks, signals, and patterns I’m seeing among founders building, exiting, and managing real capital. If that’s useful, you can subscribe here.