Investing is a long game.

Your first goal? Have enough money so you don't have to worry about it. The returns on your assets cover your expenses and lifestyle. Your number might be $1 million or $100 million.

You want to hit this goal fast.

Your second goal is protecting and growing what you've built. Now you can do what you love without working for money. You can focus on bigger ventures. You have freedom.

Here's the thing: your strategy changes completely depending on which stage you're at.

To reach goal one faster, you need focus, concentration, and willingness to take risks. Learn new skills. Grow your business. Make concentrated bets with asymmetric payoffs.

High returns come with risk. Always. Your business might fail. Your investment might crater. That's the game.

After you hit goal one, your strategy flips. Now it's about diversification, consistency, and manageable risk. You compound capital and protect it.

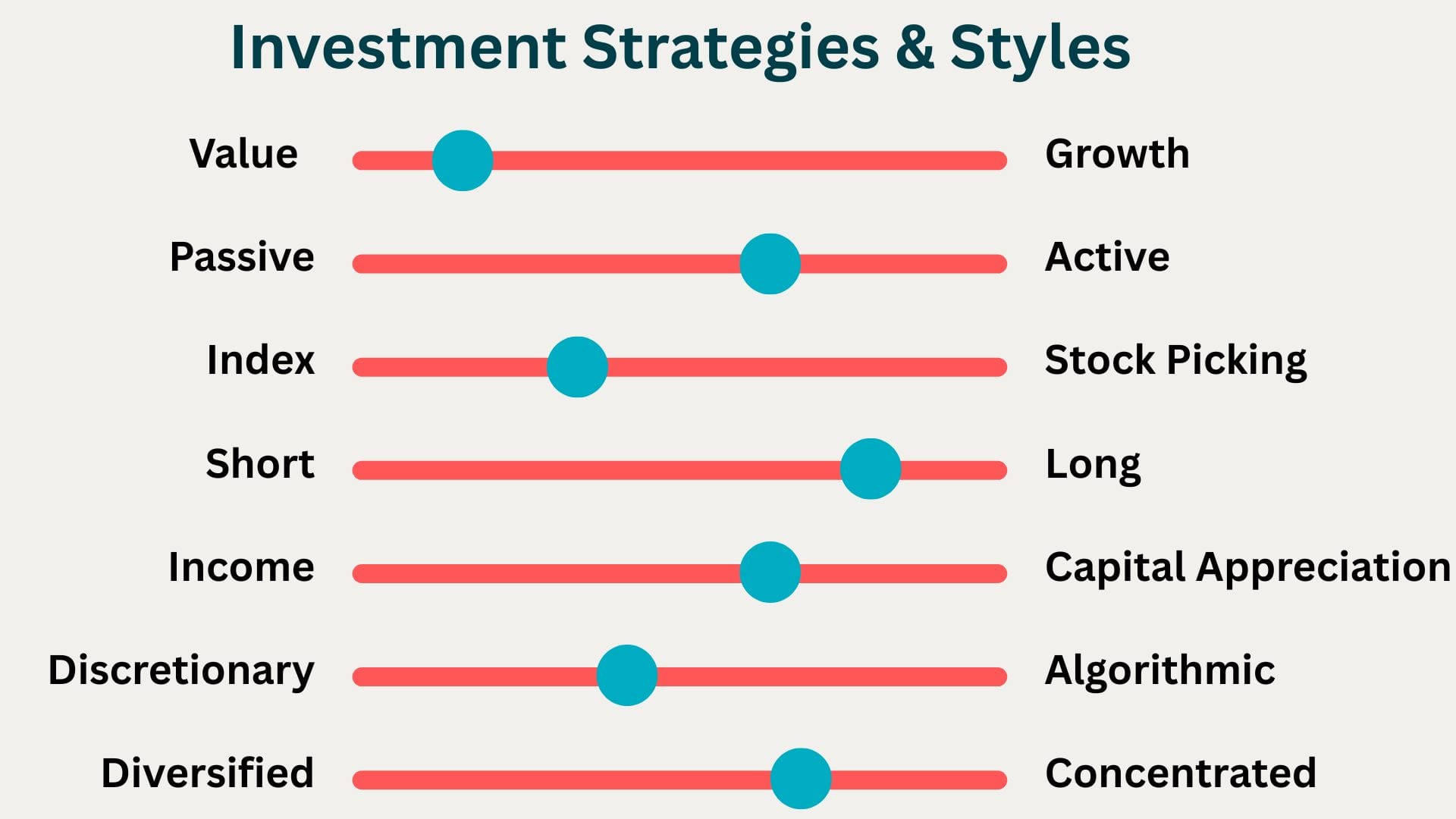

This post breaks down different investment strategies. But remember—there's no right or wrong strategy. It depends on your stage and goals.

Investments that work for some people are disasters for others. I see this constantly. People jump into investments they don't understand. It always ends badly.

If you don't understand it, don't invest in it.

Think of it like driving from London to Monaco. You want to get there fast. But drive too fast and you'll crash. It's about balance—speed, skill, and experience.

Value vs. Growth

Value investing hunts for bargains. Companies trading below what they're worth. Look for low P/E ratios, high dividends, solid assets.

Warren Buffett bought Coca-Cola in 1988 when everyone thought it was old news. He saw what others missed. His $1.3 billion investment is now worth about $28.1 billion. In 2025, Berkshire expects $816 million in annual dividends from Coke alone.

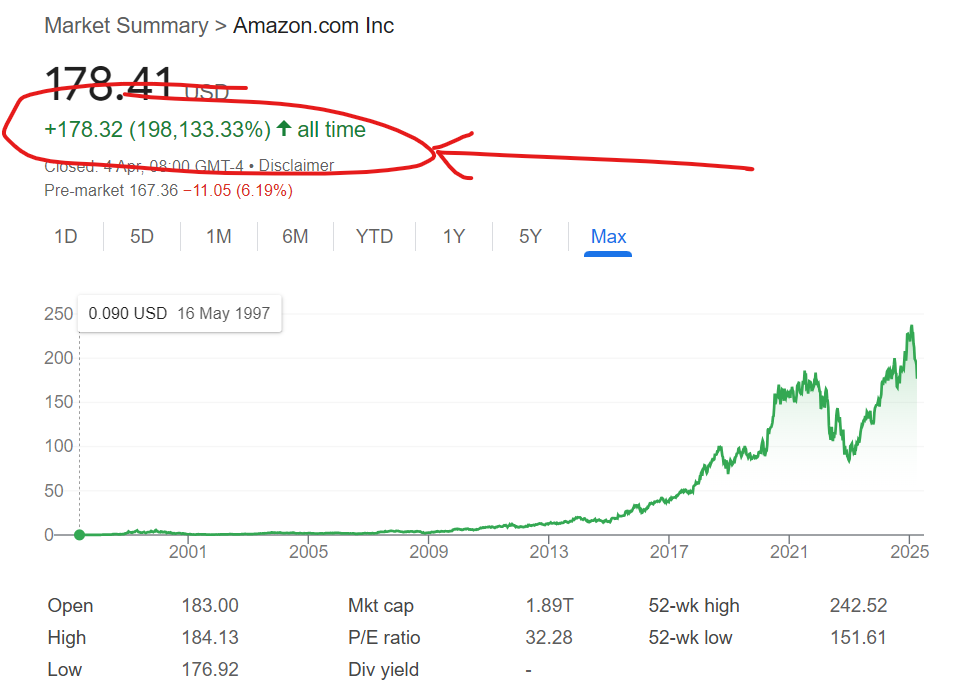

Growth investing bets on the future growth. Companies expanding rapidly, and not care about profitability that much.

Amazon barely made a profit for years. Value investors ignored it. Growth investors saw potential. Now they're rich. Growth companies trade at insane multiples. Investors accept volatility for potential moonshots.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term

Short-term trading holds positions for seconds, days, maybe weeks.

Earnings traders buy before quarterly reports. Economic data traders place leveraged bets on volatility spikes.

Long-term investing plays the long game. Years or decades.

Retirement accounts buy index funds monthly. Market swings don't matter. Compounding does the work. Pension funds hold Johnson & Johnson for 10+ years.

Active vs. Passive

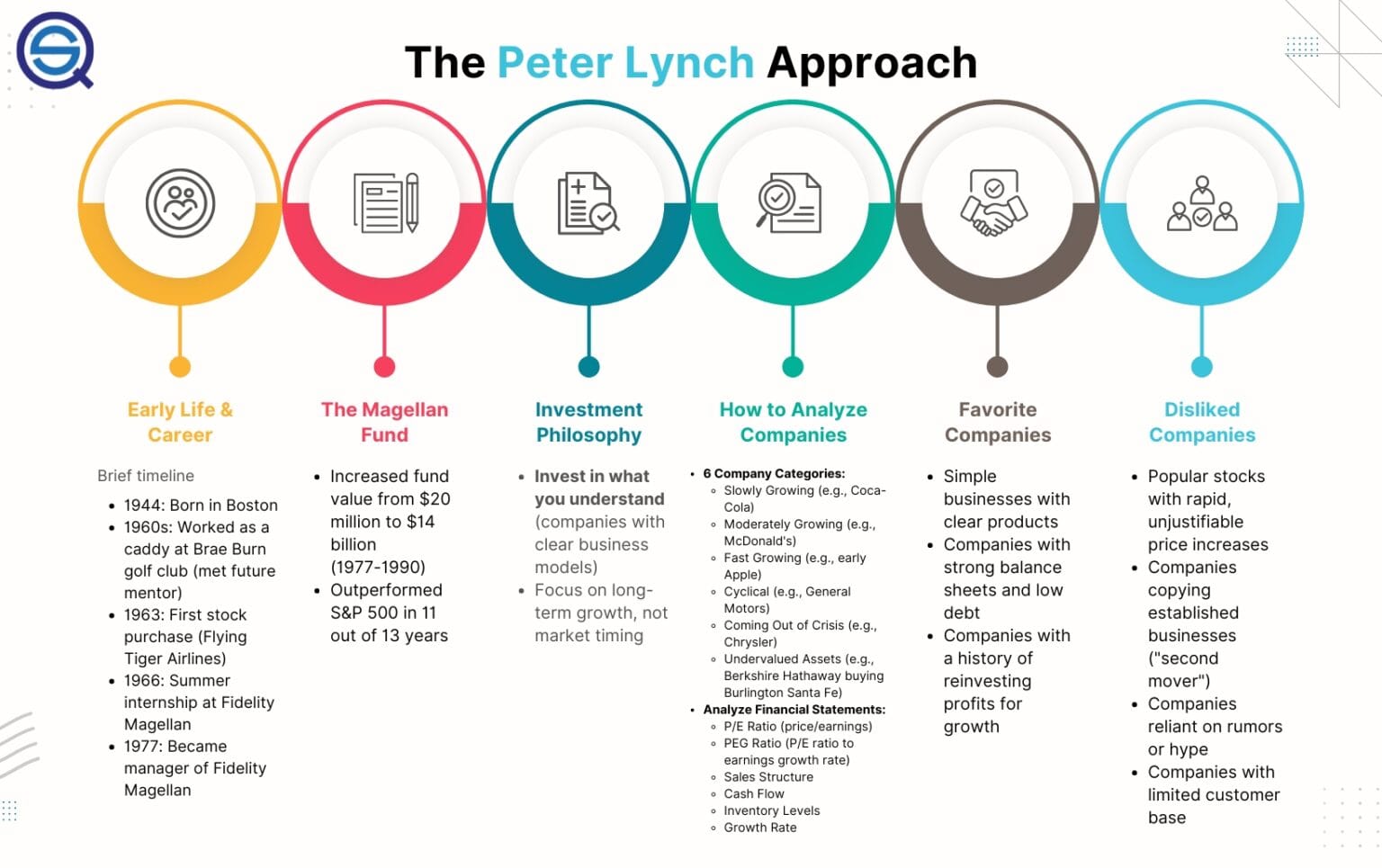

Active managers try to beat the market.

Peter Lynch ran Fidelity Magellan from 1977 to 1990. He crushed the S&P 500 through research and personal investigation. Sector funds move money between industries based on forecasts.

Passive investors match the market.

John Bogle's Vanguard index funds let you buy the market cheaply. Most active managers fail to beat index funds after fees. Today, Vanguard manages $9.3 trillion.

ETFs like SPY give you instant exposure to America's 500 biggest companies. One trade, done.

Manual vs. Algorithmic

Discretionary management uses human judgment.

Hedge fund managers travel to conferences, visit factories, meet CEOs. After months of research, they make conviction bets.

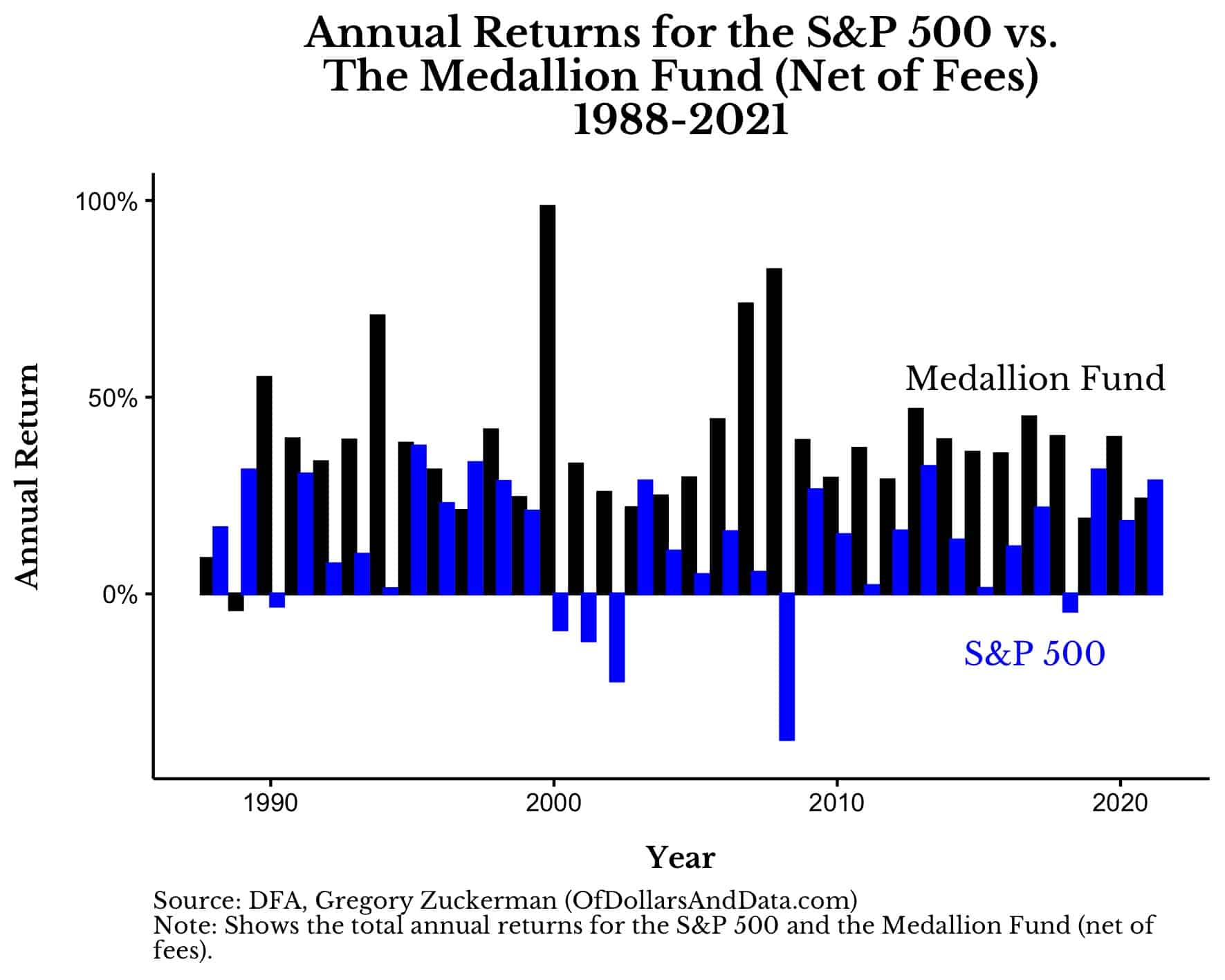

Algorithmic strategies use computers.

High-frequency traders place servers next to exchanges. They profit from microsecond price differences.

Quant funds like Renaissance Technologies analyze massive datasets. Their Medallion fund returned 66% annually before fees from 1988 to 2018. The best track record on Wall Street.

Index vs. Stock-Picking

Index investing buys the whole market at once.

Sovereign wealth funds place billions in All-World Index ETFs. Tech believers buy XLK instead of guessing which companies will win.

Stock-picking selects individual winners.

Focused managers pick obscure small-caps after deep research. Higher risk, higher reward. Activist investors like Carl Icahn target underperforming companies and push for changes.

Momentum vs. Contrarian

Momentum investors buy what's winning, sell what's losing.

Quant funds buy stocks with strong 6-12 month returns. Swing traders jump in when stocks break resistance levels.

Contrarians buy what everyone hates.

During the 2008 crisis, contrarians bought bank stocks at rock-bottom prices while others panicked. When oil futures went negative in 2020, contrarians bought energy stocks.

Fundamental vs. Technical Analysis

Fundamental analysis examines the business itself.

Before investing in pharma, analysts study clinical trials, FDA approvals, profit margins. For consumer brands like Unilever, they study brand loyalty and pricing power.

Technical analysis trades charts and patterns. Doesn't care about the company.

Forex traders spot patterns on charts and place tight stop-losses. Crypto traders watch Bitcoin break above moving averages.

Day traders love technical analysis. But one needs to be prepared to stare on screens all day long.

High-Frequency vs. Buy-and-Hold

High-frequency trading exploits microsecond opportunities.

Latency arbitrage firms receive prices faster than others. They buy at old prices, sell at new ones. Market makers profit from bid-ask spreads.

Buy-and-hold is in it for decades.

Families save for college through balanced index funds. They contribute monthly and ignore headlines. Dividend investors reinvest payouts and let compounding work.

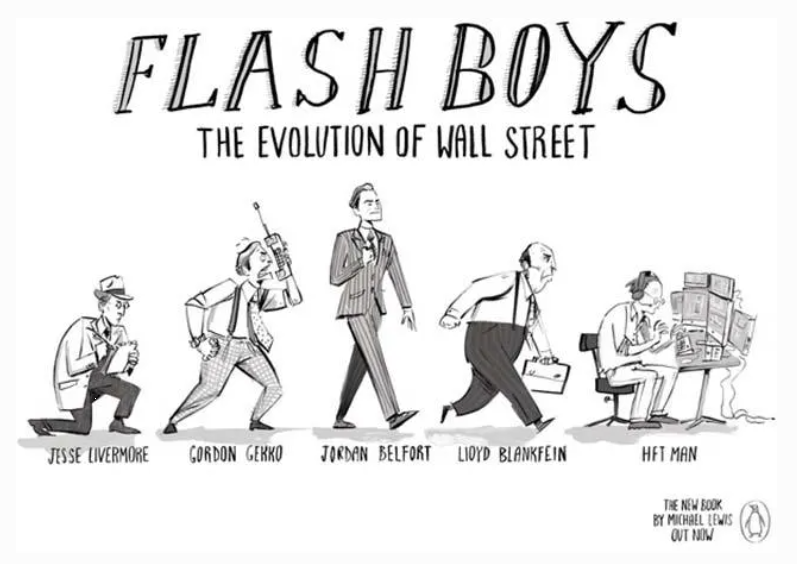

If you want to learn about the world of HFT, I highly recommend the book Flash Boys by Michael Lewis. It's fascinating! It exposes the world of high-frequency trading (HFT) and how it exploits the financial markets, often at the expense of regular investors.

Income vs. Capital Appreciation

Income investing wants regular cash flow.

Retirees buy Dividend Aristocrats—companies that raised dividends for 25+ years. Fixed-income investors structure portfolios for steady periodic income.

Capital appreciation wants growth.

Venture capital firms invest in startups with zero immediate return. They hope for a big payday years later. Growth funds hold Alphabet or Nvidia for rising stock prices.

High-Risk vs. Low-Risk

High-risk (aggressive) swings for the fences.

Crypto investors put chunks into Bitcoin or Ethereum. Extreme volatility for potential massive gains. Leveraged ETF traders use 3x products—spectacular when right, devastating when wrong.

Low-risk (defensive) prioritizes safety.

Conservative investors buy AAA-rated debt or Treasuries. Defensive players focus on utilities, healthcare, consumer staples—sectors that perform better in recessions.

Sector Rotation vs. Broad Diversification

Sector rotation times industry cycles.

Managers overweight tech during expansions. They rotate to staples and utilities before slowdowns. Commodity investors load up on energy during inflation.

Broad diversification spreads bets widely.

Classic 60/40 portfolios split between equities and bonds. Global balanced funds hold stocks and bonds from multiple countries.

Long/Short vs. Long-Only

Long/short makes money playing both sides.

Equity funds buy undervalued semis while shorting overvalued social media. John Paulson made $15 billion in 2007 shorting the housing market. Bill Ackman made $2.6 billion on a $27 million coronavirus hedge—100x return.

Market-neutral strategies maintain equal longs and shorts, targeting pure stock-picking skill with minimal market exposure.

Long-only only bets on rising prices.

Traditional mutual funds hold Apple and Disney. Dividend ETFs invest in income stocks without hedging.

Mean Reversion vs. Trend Following

Mean reversion bets extremes won't last.

Algorithms flag blue-chips that drop 10% on bad news. They buy expecting a bounce. Statistical arbitrage tracks pairs like Coke and Pepsi, trading unusual spreads.

Trend following bets momentum continues.

Managed futures scan commodities for market trends. They go long gold or oil until indicators suggest a reversal. Traders buy stocks hitting 52-week highs with volume.

Thematic vs. Broad Market

Thematic investing targets specific trends/industries/themes.

AI-related stocks like Nvidia. Cybersecurity ETFs expecting demand growth. Clean energy or Defence plays.

Broad market wants everything.

Total market index funds invest in thousands of companies across sectors. Global indices hold stocks from developed and emerging markets.

Leveraged vs. Unleveraged

Leveraged uses borrowed money to amplify returns.

Hedge funds might borrow $1 billion against $1 billion in capital. Leveraged ETFs offer 2x or 3x daily exposure - up and down.

Unleveraged only risks what you put in.

Traditional buyers use only available capital. Conservative retirees avoid margin calls and forced liquidations.

Absolute Return vs. Relative Return

Absolute return aims to profit regardless of conditions. Hedge fund territory.

Global macro funds go long one country's bonds, short another's currency. Multi-strategy funds combine approaches for steady performance.

Relative return measures against benchmarks.

If the S&P 500 falls 10% but your fund falls 8%, you outperformed by 2%. That's considered good. Institutional investors often target "3% above MSCI World."

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

Top-down starts with the big picture.

Global outlook, then country, industry, sector, companies. Macro managers seeing rising rates short Treasuries and buy Japanese exporters. Emerging market investors spot GDP growth and focus on consumer plays.

Bottom-up starts with individual companies.

Small-cap analysts research unknown medical device makers. They interview doctors and scrutinize tests. Stock-specific investors buy retailers with strong e-commerce regardless of sector sentiment.

Cyclical vs. Defensive

Cyclical bets on boom times.

Airlines surge during expansions. Luxury goods like LVMH and Ferrari benefit when consumers have cash but drop when spending tightens.

Defensive wants stability.

Utilities like Duke Energy see consistent demand. Pharma like Pfizer and J&J remain steady during recessions.

Concentrated vs. Highly Diversified

Concentrated makes a few big bets.

Activist funds put 20-30% into one or two companies. Thematic investors go all-in on AI or EVs. Massive gains or painful losses.

High diversification spreads bets widely.

Global funds hold hundreds of securities across stocks, bonds, real estate. Core/satellite portfolios allocate most to broad indices with smaller risky positions.

Illiquid vs. Liquid

Illiquid (private markets) locks up capital for higher returns.

Private equity buys manufacturing companies, boosts profitability, sells years later. VC funds make early Uber or Airbnb bets, accepting 5-10 year lockups.

Reality of a typical VC portfolio:

- Failures: 25-30%

- Break-even: 30-40%

- High returns (2x-10x): 20-25%

- Unicorns (>10x): 2-10%

Understand this: you won't get your money back for years.

Liquid (public market) exits quickly.

Sell Apple or Microsoft within seconds. Bond ETF holders trade quickly despite underlying illiquidity.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

Quantitative (factor-based) relies on numbers and models.

About 60-75% of U.S., European, and Japanese equity trading is quantitative. Smart beta ETFs select stocks based on factor scores. Machine learning funds use AI to detect patterns.

Discretionary means humans make final decisions.

Early Tesla investors believed in Musk's vision despite uncertain financials. Brand-focused managers invest in Nike based on cultural resonance.

Putting It Together

We've covered a lot. But this barely scratches the surface.

An investment strategy is a building block. Your portfolio is the structure you build.

Different strategies succeed in different conditions. That's normal. That's why you blend approaches.

Your strategy must match:

- Your time horizon

- Your risk tolerance

- Your financial goals

- Your personal values

There's no perfect strategy for everyone. The best strategy is one you understand and stick with through market cycles.

Now get in the game and start playing.