Before diving into specific strategies, we need to address something that creates real confusion.

There's a difference between an investment strategy and portfolio management. An investment strategy is a single approach to generating returns, such as value investing, momentum trading, or private equity etc. Portfolio management is how you combine these building blocks into a coherent whole.

The financial industry often conflates these two things. Professional fund managers at established institutions won't usually make bold claims about their strategy being a complete solution. But you will encounter people pitching "unique" strategies to private investors, often comparing their approach to a 60/40 portfolio and promising superior returns. Sometimes it's someone running a small fund. Sometimes it's an individual with a proprietary system. The pitch usually involves showing backtested returns or cherry-picked performance periods.

These pitches can be compelling. They're also incomplete.

It's more complex than that. Different strategies perform differently in various market conditions. Value stocks dominated from 2000 to 2006. Growth stocks crushed everything from 2010 to 2021. Bonds provided ballast for decades, then lost 13% in 2022. Private equity looked brilliant when interest rates were zero, then struggled when capital became expensive.

No single strategy wins all the time. This is precisely why understanding how to combine strategies matters more than finding the "best" one that "prints money".

Working with a qualified financial adviser or wealth manager can help here. Someone who isn't tied to selling a specific product can think about your portfolio holistically: what individual strategies make sense given your situation, how to weight them, when to rebalance, and how everything fits your goals.

But even if you work with an adviser, understanding the building blocks yourself is valuable. You'll ask better questions. You'll spot when something doesn't make sense. You'll be an informed participant in decisions about your own capital.

Key Takeaways

- Investment strategies are building blocks. Portfolio management is how you combine them. Confusing the two leads to expensive mistakes.

- No strategy wins all the time: Value dominated 2000–2006. Growth crushed 2010–2021. Bonds lost 13% in 2022. Diversification across strategies smooths returns.

- Active management statistics: 65% of managers underperform over 1 year, 84% over 10 years, 92% over 20 years. Even Peter Lynch's fund became average after he left.

- Factor premiums require patience: Value, momentum, and quality factors can underperform for years. The premiums are most reliable over 10–15 year horizons.

- Tax-loss harvesting: Can add 1–2% in after-tax returns annually. 80% of benefits come in the first five years. Direct indexing captures 2.5x more losses than ETFs.

- Rebalancing approach matters: Threshold-based (20% bands) outperforms calendar-based. Look frequently, trade rarely.

- Asset allocation trumps strategy selection: How you divide capital among stocks, bonds, and alternatives explains most of portfolio return variation. Work with an adviser who thinks holistically, not one selling a single strategy.

Value vs. Growth

These are two different approaches to generating returns. They tend to perform differently depending on market conditions.

Value Investing

Value investors hunt for bargains. They look for companies trading below intrinsic value, often measured by low price-to-earnings ratios, high dividend yields, or solid book values that the market is ignoring.

Warren Buffett's Coca-Cola position remains the textbook example. He began accumulating shares in 1988 when most institutional investors considered the company boring and mature. His eventual $1.3 billion investment (accumulated through 1994) is now worth approximately $28 billion. More striking: Berkshire Hathaway received $816 million in dividends from Coca-Cola in 2025 alone. That's roughly 63% of his original investment returned in cash every single year.

The value approach requires patience and the temperament to buy what's unloved. When a stock is cheap, there's usually a reason. Sometimes that reason is temporary. Sometimes it isn't. Telling the difference is the hard part.

Growth Investing

Growth investors care less about current valuation and more about future potential. They're willing to pay premium prices for companies expanding rapidly, even if those companies aren't yet profitable.

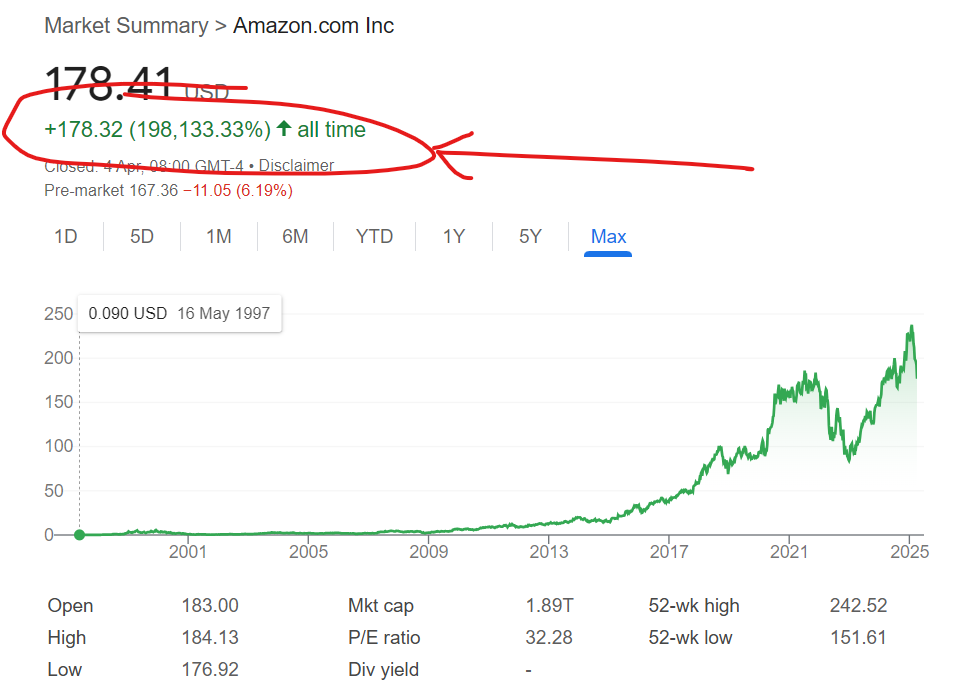

Amazon operated at razor-thin margins for decades. Traditional value investors couldn't stomach the valuation. Growth investors saw the potential and held on. The same story played out with Tesla, Netflix, and more recently with AI-related companies.

Growth investing accepts volatility as the price of admission. These stocks can drop 50% on a disappointing earnings report. They can also double in a year when expectations are exceeded.

How Academic Research Sees This

The value premium is one of the most studied phenomena in finance. Eugene Fama and Kenneth French documented that value stocks have historically outperformed growth stocks over long periods. From 1963 to 2024, the value factor generated an annualized return premium of approximately 2.9%, according to data from the Kenneth R. French Data Library.

But there's a catch. Value stocks dramatically underperformed from roughly 2007 to 2020. Anyone who committed to pure value investing during that stretch endured years of watching growth stocks soar while their portfolio lagged. The premium exists over very long periods, but individual decades can look completely different.

Active Trading vs. Buy-and-Hold

This distinction is really about time horizon and what you believe about market efficiency.

Active (or Day) Trading

Active traders try to profit from short-term price movements. Day traders hold positions for minutes or hours. Swing traders might hold for days or weeks. The belief underpinning this approach: markets are inefficient enough in the short term that skilled traders can consistently profit from price discrepancies, news reactions, earnings surprises, or technical patterns.

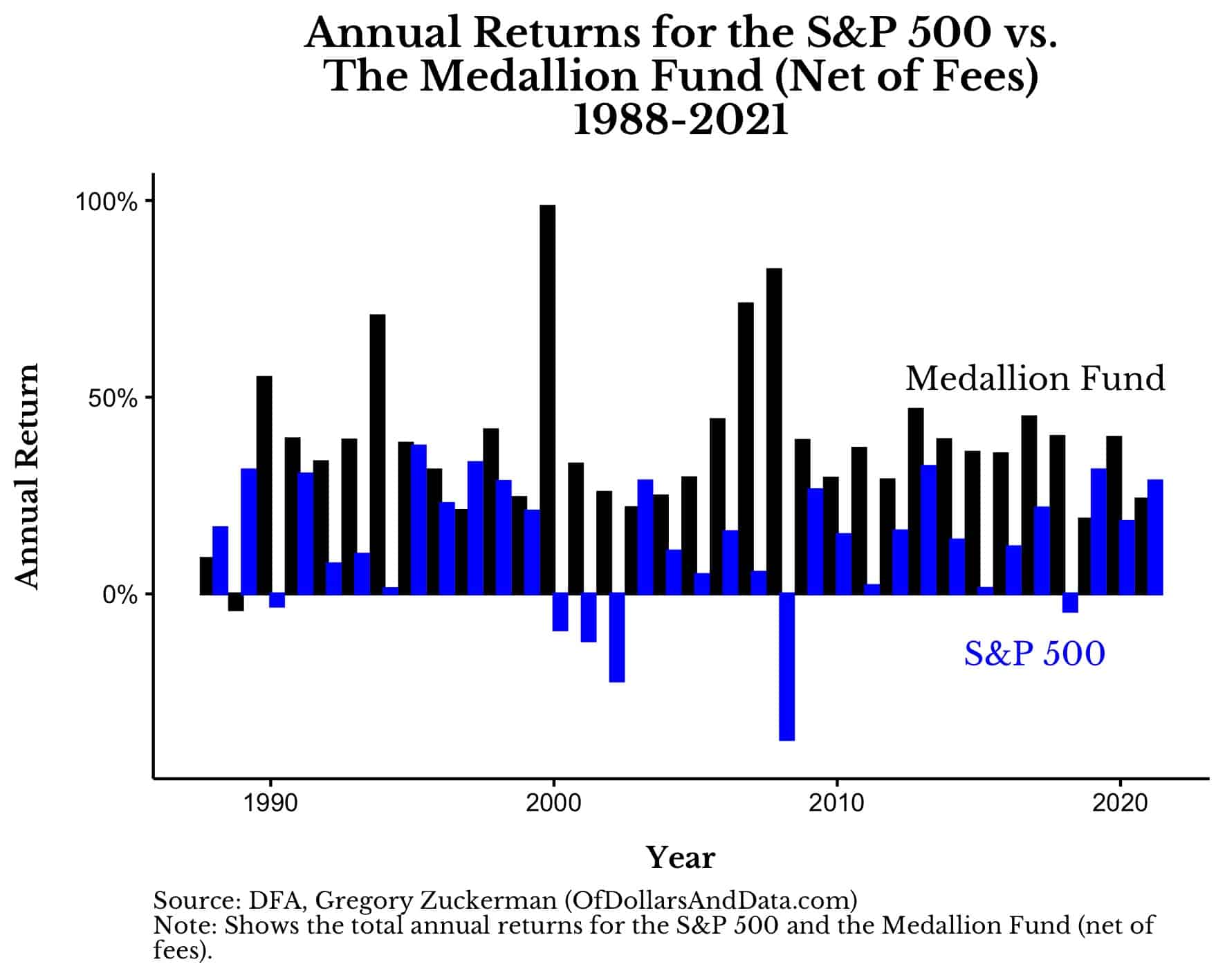

Renaissance Technologies' Medallion Fund represents the extreme end of what's possible. The fund returned roughly 66% gross (39% net of fees) annually from 1988 to 2018, with no negative years. They achieve this through quantitative strategies that identify and exploit tiny inefficiencies across millions of trades. Their win rate is reportedly around 50.75%. A tiny edge, compounded millions of times.

The statistical picture for active trading is stark: for every Renaissance, there are thousands of funds and traders who underperform. S&P Dow Jones publishes annual SPIVA scorecards comparing active managers against their benchmarks. The 2024 data shows 65% of large-cap fund managers underperformed the S&P 500 over one year. Over ten years, 84% underperformed. Over twenty years, 92% failed to beat the index.

The statistical evidence against most active trading is overwhelming. Some managers have genuine skill. Most don't. And identifying the skilled ones in advance is nearly impossible.

Buy-and-Hold

Buy-and-hold investing takes the opposite view. If most active trading destroys value after costs, and if markets generally rise over time, then the optimal strategy is to buy diversified assets and hold them through market cycles.

Index funds embody this philosophy. John Bogle founded Vanguard on the principle that most investors would be better off simply owning the market at low cost. Today, Vanguard manages $11 trillion in assets. The approach has been validated by decades of data.

Buy-and-hold requires a different kind of temperament than trading. You have to sit through crashes without selling. You have to ignore the noise. In March 2020, markets dropped 34% in about a month. Buy-and-hold investors who stayed the course recovered within six months. Those who panicked and sold locked in losses.

Active vs. Passive

This is related to trading vs. buy-and-hold, but applies specifically to how investment funds operate.

Active Management

Active managers research companies, make investment decisions, and try to outperform a benchmark. They charge higher fees for this effort, typically 0.5% to 2% annually for mutual funds, sometimes more for hedge funds.

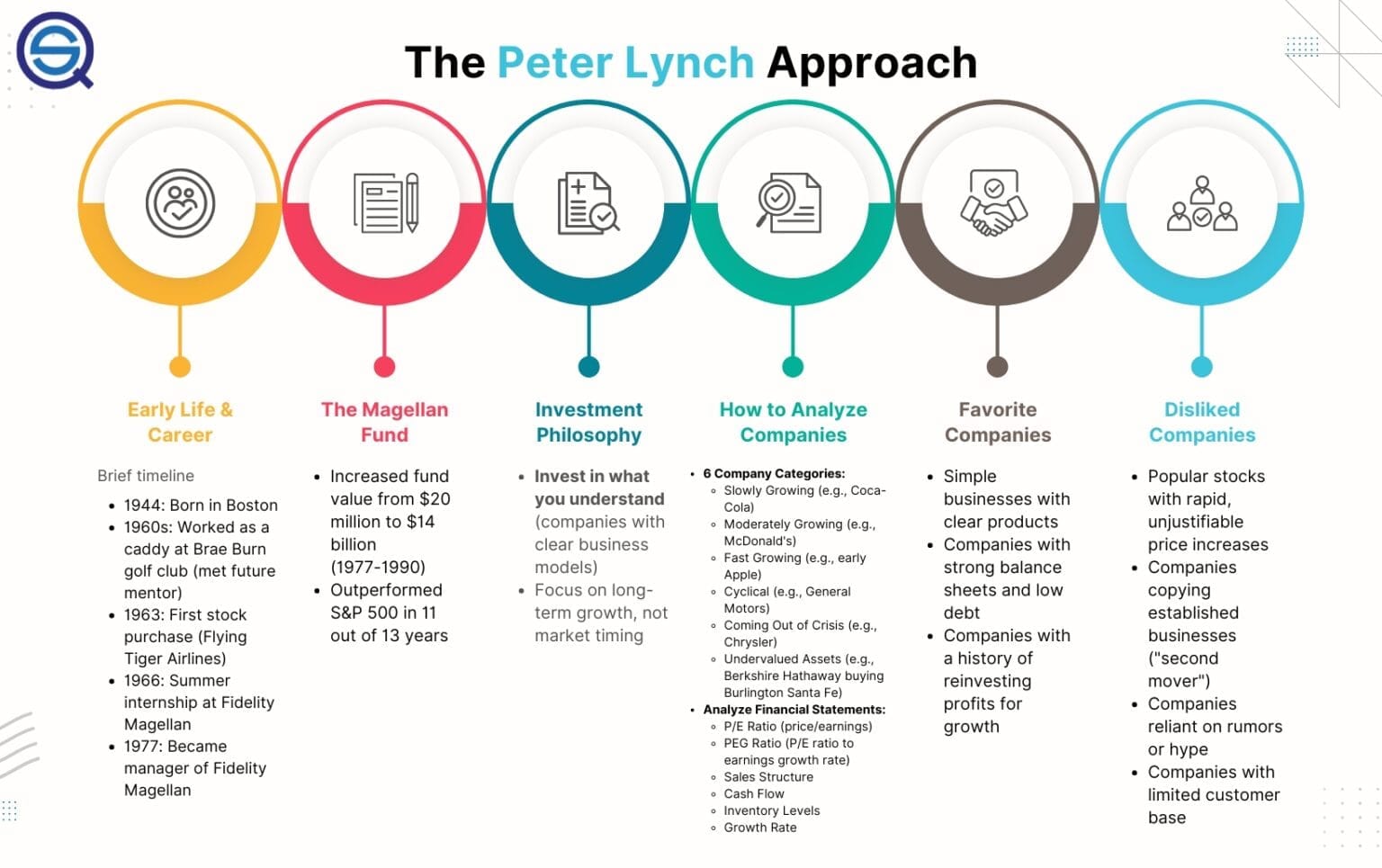

Peter Lynch ran Fidelity Magellan from 1977 to 1990, returning 29% annually and crushing the S&P 500. He did it through fundamental research, visiting companies, talking to management, and finding opportunities others missed.

Today, millions of private investors try to copy his stock-picking principles.

But Lynch retired in 1990. He was 46. He hasn't managed money since. And the times (and market conditions) are very different now.

What happened after he left is instructive. The Magellan Fund became thoroughly ordinary. Under Bob Stansky (1996-2005), the fund returned 238% while the S&P 500 returned 274%. Today, Morningstar describes it as "an unremarkable 3-star large-growth fund, slightly lagging its category average over the trailing 10 years."

Lynch's track record is historical. It tells us that exceptional performance was possible in a particular era, when retail stockbrokers and their clients dominated equity trading. It doesn't tell us who will outperform going forward.

Passive Management

Passive funds simply track an index. No research. No stock-picking. Just a mechanical replication of whatever benchmark they follow. Fees are minimal, often 0.03% to 0.20% annually.

The logic is straightforward: if active managers as a group underperform after fees, and if you can't reliably identify the exceptions in advance, then just own the market at the lowest possible cost.

This approach has won the debate for most investors. The vast majority of money flowing into equity funds now goes to passive strategies. That doesn't mean active management is worthless for everyone, but the burden of proof has shifted. You need a specific reason to choose active management, not a reason to choose passive.

QUICK ASK — Everything here is free. If you're finding this useful, subscribing helps me understand what's working — and keeps you updated when new pieces come out.

Factor Investing

Factor investing takes academic research on stock returns and applies it systematically. Rather than just "value" or "growth," researchers have identified several characteristics associated with higher returns over time.

The Primary Factors

Value: Cheap stocks relative to fundamentals (book value, earnings, cash flow) tend to outperform expensive ones. Since 1963, the value factor has generated an annualised premium of approximately 2.9% over the market.

Momentum: Stocks that have performed well over the past 3-12 months tend to continue performing well in the short term. Research spanning 150 years and 40 countries confirms this pattern persists, though it comes with occasional violent reversals.

Quality: Companies with high profitability, stable earnings, and low debt tend to outperform low-quality firms. The quality factor has shown strong and stable performance across market cycles.

Size: Small-cap stocks have historically outperformed large-caps, though this premium has weakened in recent decades.

Low Volatility: Counterintuitively, less volatile stocks have delivered better risk-adjusted returns than high-volatility stocks. This anomaly persists despite challenging efficient market theory.

Multi-Factor Approach

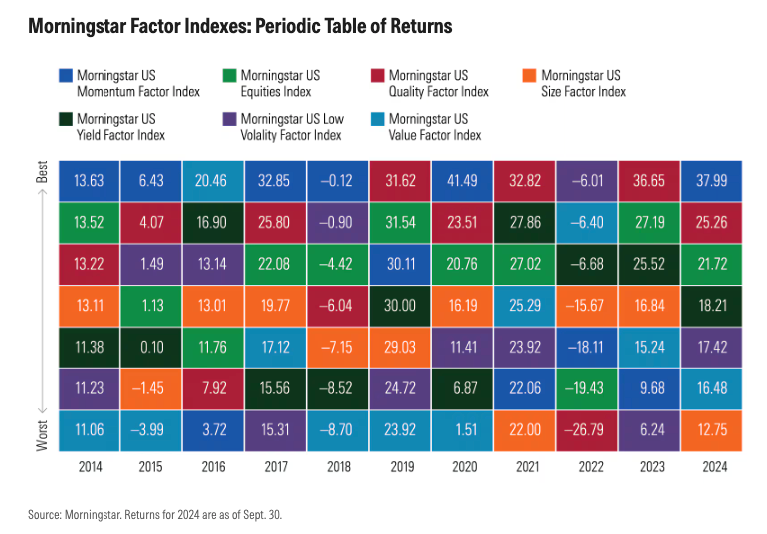

Individual factors go through extended periods of underperformance. Value struggled from 2007 to 2020. Momentum crashes periodically during market reversals. Quality lagged during speculative rallies.

The insight is that these factors have low or negative correlations with each other. When value is struggling, momentum might be thriving. When quality lags, low volatility might outperform. Combining multiple factors into a single portfolio can smooth returns without necessarily sacrificing the long-term premium.

According to Morningstar's research, calendar-year returns for individual factors show dramatic variation. In 1998-1999, momentum dramatically outperformed while low volatility returned single digits. In 2000, momentum crashed and low volatility surged. Factor diversification reduces the risk of being on the wrong side of these swings.

Factor investing typically requires longer time horizons. These premiums are most robust over 10-15-year periods. Investors looking for shorter-term results may find factor tilts frustrating as they underperform for years at a stretch.

Concentrated vs. Diversified

How many positions should a portfolio hold? This is more philosophical than it might appear.

Concentrated Investing

Some investors believe strongly in concentration. Buffett famously said that diversification is protection against ignorance and that it makes little sense for those who know what they're doing.

Concentrated investors might hold 10-20 positions. They know each company deeply. When they're right, returns can be spectacular. But when they're wrong, losses compound just as quickly.

The extreme case: your career is already a concentrated bet on one company, one industry, one geography. For founders, especially, significant wealth is often tied to a single business. Adding more concentration to financial assets increases the overall risk profile.

Broad Diversification

Modern portfolio theory demonstrates that diversification reduces risk without necessarily reducing returns. By spreading capital across many positions, sectors, and geographies, you reduce the impact of any single investment failing.

The Global Diversified Portfolio (60% stocks, 40% bonds across multiple countries) has been the institutional standard for decades. It won't produce spectacular returns in any single year, but it reduces the probability of devastating losses.

Research from Vanguard suggests 40% of your stock holdings in international equities provides meaningful diversification benefits. The US market won't always dominate. Different economies move through various market cycles.

For most investors, especially those who've built wealth through concentrated business success, diversification after exit is protective. You've already taken concentrated risk and won. Preserving that outcome through broad diversification is a different game with different rules.

Geographic Allocation

Most investors over-allocate to their home country. US investors typically hold far more domestic stocks than global market caps would suggest. UK investors do the same. This is called "home bias."

The Case for International Diversification

The US currently comprises approximately 64% of the MSCI All-Country World Index. A market-cap-weighted global portfolio would allocate roughly 60% to domestic stocks and 40% to international stocks for US investors.

Why bother with international exposure? Because markets don't move in lockstep. When US stocks struggle, European or emerging market stocks might thrive. Currency movements add another dimension of diversification.

Goldman Sachs research suggests the World Portfolio is currently overweight US equities compared to historical norms. Their models indicate US stocks would need to outperform non-US equities by 4-5% annually over the next decade to justify current allocations. That's possible but aggressive.

Vanguard's projections suggest a 60/40 portfolio with market-cap weighted international exposure would return 0.6 percentage points more annually and have 0.4% less volatility than a domestic-only portfolio over the next decade.

Practical Considerations

Currency risk cuts both ways. International holdings denominated in foreign currencies can add volatility. Some investors hedge currency exposure; others accept it as part of the diversification.

Transaction costs and taxes matter. Investing internationally can be more expensive. Some jurisdictions have withholding taxes on dividends. These frictions don't eliminate the diversification benefit, but they reduce it.

Private Markets: Illiquidity Premium

Private equity, venture capital, and direct real estate operate differently from public markets. You can't sell tomorrow. Your capital is locked up for years. In exchange, you might earn higher returns.

Private Equity

Private equity funds buy companies, improve operations, and sell them years later. The strategy relies on active ownership, leverage, and time. According to Preqin, private equity has been the best-performing alternative investment class over the past two decades.

Family offices now allocate approximately 27% of assets to private equity, making it their second-largest allocation after public equities at 29%.

But private equity comes with significant complications. Fees are higher (typically 2% management fee plus 20% of performance). Capital is locked for 7-10 years. Performance dispersion is wide: top-quartile managers dramatically outperform bottom-quartile. Selecting the right managers matters enormously.

Venture Capital

Venture capital represents the extreme end of private market investing. Most startups fail. The math depends entirely on outliers.

Typical VC portfolio outcomes: 25-30% failures (total loss), 30-40% break-even, 20-25% return 2-10x, and only 2-10% become unicorns returning 10x or more. About 67% of seed-funded startups stall before reaching Series B. Roughly 1% reach unicorn status.

Only 15-20% of VC funds generate returns that actually justify the illiquidity premium. Manager selection is critical and complex. Access to top funds is often limited.

Real Estate

Real estate provides income, appreciation potential, and inflation protection. It's tangible in a way stocks and bonds aren't. Family offices allocate approximately 15% to real estate and tangible assets.

You can access real estate through direct ownership, private funds, or public REITs. Each comes with different liquidity, fee structures, and tax implications. Direct ownership requires active management or hiring managers. REITs trade like stocks but lose some of the uncorrelated characteristics.

Alternative Assets

Beyond traditional private markets, high-net-worth investors are increasingly allocating to alternative assets.

Current Allocation Trends

Ultra-high-net-worth investors (those with $30M+) now allocate approximately 20% to alternatives, compared to near-zero for average investors. High-net-worth investors have increased alternative allocations to 28% in recent years, up from earlier periods.

The shift reflects several factors: low yields on traditional bonds, elevated stock valuations, and a desire for uncorrelated returns. Alternatives don't consistently deliver, but they can provide different risk exposures than stocks and bonds alone.

What Counts as Alternative

Private credit has expanded rapidly as banks pulled back from lending. These strategies offer yield premiums over public bonds in exchange for illiquidity and credit risk.

Hedge funds use various strategies (long/short equity, global macro, event-driven) to generate returns uncorrelated with markets. Performance varies dramatically by strategy and manager. The category has disappointed many investors since 2008, though specific funds still deliver.

Commodities (gold, energy, agricultural products) can hedge inflation and provide diversification. Gold in particular tends to perform well during market stress.

Collectables (art, wine, cars, watches) have attracted wealth preservation capital. These are illiquid, require expertise, and generate no income. Returns depend entirely on finding buyers willing to pay more later.

Tail Risk Strategies

Some investors allocate specifically to strategies that profit during market crashes (also called Black Swan events). These are often expensive insurance policies that lose money in normal years.

How Tail Risk Protection Works

Tail risk strategies typically involve buying options that pay off during extreme market declines. A portfolio might allocate 1-5% to these positions, expecting to lose most or all of that allocation in normal years while gaining substantially during crashes.

Bill Ackman's famous COVID hedge exemplified this. He spent $27 million on credit protection in February 2020. When markets crashed in March, that position was worth $2.6 billion. A 100x return. But you need to remember that it was the return on his hedging position. It was relatively small in his overall portfolio, which most likely suffered significant losses during this time.

John Paulson's 2007 housing short is perhaps the most famous tail risk trade ever. He made approximately $15 billion betting against subprime mortgages as the housing bubble collapsed.

The Cost of Protection

Tail risk strategies are expensive over time. If you buy put options every year for ten years and markets rise, you'll have spent significant capital on protection that never paid off.

According to bfinance research, institutions typically dedicate 0.5-1% of portfolio value annually to hedging costs. The goal is partial protection (covering the first 10-15% of drawdown) rather than total protection, which would be prohibitively expensive.

Alternatives to explicit tail hedging include: holding more cash, diversifying into uncorrelated assets, using trend-following strategies that naturally reduce exposure during downturns, and simply accepting that drawdowns are part of investing.

AQR's research suggests that for investors who can modify portfolio structure and policy, reducing total market exposure may be more efficient than buying tail insurance. The expected return from buying perpetual insurance is negative.

Tax-Loss Harvesting

Tax-loss harvesting involves selling positions at a loss to offset capital gains elsewhere in your portfolio. It's one of the clearest value-adds available to taxable investors.

How It Works

When you sell an investment for less than you paid, you realise a capital loss. This loss can offset capital gains from other investments. Unused losses can offset up to $3,000 of ordinary income annually and carry forward indefinitely.

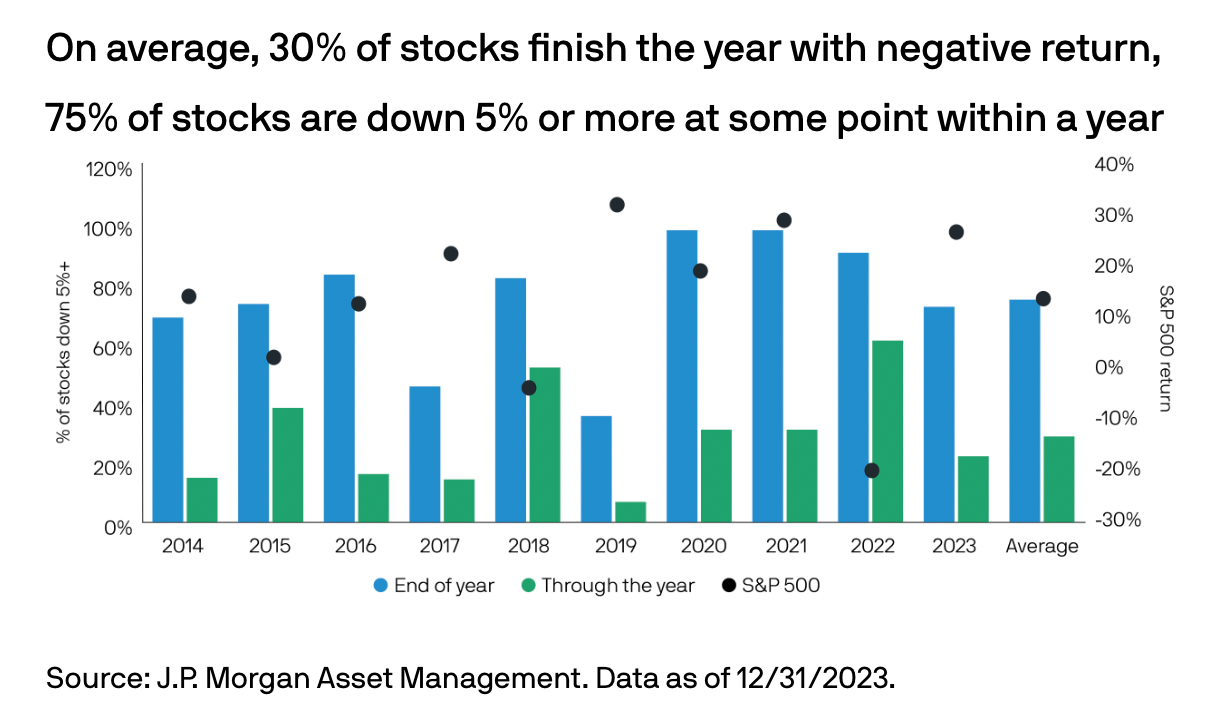

The strategy works best in volatile markets where individual positions frequently trade below cost basis. Even in rising markets, individual stocks often decline. Research shows that 75% of stocks fall more than 5% at some point during the year, even when markets finish positive.

Quantifying the Benefit

MIT research found that tax-loss harvesting in a diversified US equity portfolio harvested approximately 60% of the initial investment value over 20 years. Assuming losses offset short-term gains taxed at 40%, the annualised benefit was approximately 1.2%.

Third-party research suggests tax management can add 1-2% in after-tax excess returns for equity portfolios and 0.3% for fixed income.

Best Practices

Daily monitoring outperforms calendar-based approaches. Continuous monitoring captures short-term volatility that monthly or quarterly reviews miss.

Direct indexing (owning individual stocks rather than funds) provides more harvesting opportunities than ETFs. Morningstar research found stock portfolios realised 2.5 times the losses of ETF portfolios over five years, with long-term equilibrium harvest yields 4 times higher.

Benefits are front-loaded. J.P. Morgan research shows 80% of cumulative tax savings typically occur within the account's first five years. Ongoing contributions help maintain harvesting opportunities.

Portfolio Rebalancing

As markets move, your portfolio drifts from target allocations. Rebalancing brings it back. This sounds mechanical, but the approach you choose matters.

Why Rebalancing Matters

Without rebalancing, a portfolio gradually becomes dominated by whatever has performed best. After a long bull market, a 60/40 portfolio might drift to 80/20. That's more risk than intended. When markets reverse, the portfolio falls harder than expected.

Rebalancing also enforces a "buy low, sell high" discipline. You're systematically selling what's risen and buying what's fallen. This feels counterintuitive in the moment but tends to improve long-term outcomes.

Calendar vs. Threshold Approaches

Calendar-based rebalancing adjusts portfolios at set intervals (monthly, quarterly, annually). It's simple and systematic. The downside: you might rebalance when nothing has moved much or miss urgent corrections during volatile periods.

Threshold-based rebalancing triggers when allocations drift beyond set bands (typically 5-20% relative deviation). This approach trades less frequently and can respond faster to extreme moves. During COVID's March 2020 crash, Vanguard research shows threshold-based portfolios would have drifted only 2% from target, while monthly calendar-based portfolios drifted 7%.

What Research Suggests

Vanguard's analysis found that monthly calendar rebalancing offers no improvement in long-term risk or returns over annual rebalancing. It simply increases turnover and transaction costs.

Research on threshold-based approaches suggests a 20% relative band with frequent monitoring (daily or weekly) captures most benefits while minimising unnecessary trades. Looking frequently but trading rarely is the core insight.

For taxable accounts, rebalancing through new contributions (directing cash to underweight asset classes) avoids realising gains. Using tax-advantaged accounts for more frequent rebalancing minimises tax drag.

Matching Strategies to Your Situation

Understanding strategies intellectually is different from knowing which to use. Each strategy has a potential role in a portfolio, but appropriate weights depend on your specific circumstances.

Key Questions

What's your time horizon? If you need money in two years, volatility matters enormously. If your horizon is 30 years, short-term volatility matters less. Private markets require 7-10 year lockups. Momentum strategies can underperform for years. Factor premiums are most reliable over 10-15 years.

What's your actual risk capacity? This is different from risk tolerance. Risk capacity is what you can afford to lose without destroying your financial plan. A retiree living off portfolio income has low risk capacity regardless of psychological tolerance. A working professional with decades of earnings ahead has a higher capacity.

Do you have an informational or analytical edge? Most investors don't. If you've spent your career in biotech, you might reasonably tilt toward healthcare investments. If you've operated in private markets, you understand those dynamics. Edge comes from genuine expertise, not enthusiasm.

What's already in your portfolio? If your wealth is concentrated in one company or sector, diversification becomes more important. If you have significant real estate exposure, you might not need more. Portfolio construction considers everything you own, not just financial assets.

Why Asset Allocation Matters More Than Strategy Selection

Academic research consistently shows that asset allocation (how you divide capital among stocks, bonds, and alternatives) explains most of the variation in portfolio returns. Security selection within asset classes matters less than getting the overall mix right.

This is why working with a qualified adviser who thinks holistically about your situation is valuable. Someone selling a single strategy has inherent conflicts. An adviser focused on overall asset allocation can help construct a portfolio from building blocks that fit together.

Chasing strategies that promise higher returns without considering how they fit your situation is genuinely dangerous. The highest-returning strategy over the past decade may be the worst choice for the next decade. The strategy your neighbour swears by may not match your goals at all.

What Founders Often Get Wrong

Founders who've built and exited companies face specific challenges when transitioning to investor mode.

Pattern Recognition Doesn't Always Transfer

The pattern recognition that made you successful as an operator can mislead you in investing. Building a company rewards conviction, speed, and concentrated bets. Portfolio management often rewards diversification, patience, and humility in the face of uncertainty.

DALBAR's research shows equity investors earned 6% annually over 20 years while the comparable index returned 8.3%. The difference isn't bad strategy selection. Its behaviour: buying high, selling low, getting impatient with strategies that are temporarily underperforming.

Case Study: Managing Concentrated Wealth

Cambridge Associates describes a pharmaceutical entrepreneur who built a $100+ billion public company and held concentrated stock. The entrepreneur believed in the company's prospects but needed liquidity and stability.

The solution wasn't to sell everything and go to index funds. Instead, they constructed a portfolio of diversifying strategies (multi-strategy hedge funds, global macro, trend-following, specialised credit) with near-zero or negative correlation to equity markets. This provided ballast and liquidity while maintaining the concentrated growth engine.

The point isn't that everyone should own hedge funds. The point is that portfolio construction for wealthy individuals with concentrated positions requires considering correlations, liquidity, and how the different pieces work together.

Insights from Founders Who've Done This

The MoneyWise podcast (Sam Parr and Harry Morton, produced by Hampton) features founders discussing their portfolios with unusual transparency. Common themes:

Several founders describe allocating to index funds (systematic factor-based approach) plus small positions in Bitcoin or other speculative assets. Many also allocate to private credit to generate consistent returns and cover the cost of living. The core is boring; the edges are interesting.

Private deals often "feel better than they perform." The emotional satisfaction of being in an exclusive investment doesn't correlate with returns. Several founders admit this bias but find it hard to resist.

The "headline number" from exits rarely reflects what founders actually take home. After taxes, deal structure, earnouts, and other complications, the final number is often much smaller.

I highly recommend listening to this podcast, as it focuses explicitly on founders post-exit, i.e., those who have already made money. You could hear some interesting stories, learn some useful lessons, and hear some crazy mistakes others made. I am sure it will help you to become a better investor.

Building Your Strategy Framework

Rather than prescribing a specific allocation, consider a decision framework.

Start With Core Holdings

For most investors, the core of a portfolio should be broadly diversified, low-cost, and passive. Global stock index funds. Government and investment-grade bonds. Simple, boring, effective.

This core provides market exposure without requiring stock-picking skill, factor-timing ability, or manager selection. It's the default that evidence suggests most investors should favour.

Add Tilts Where You Have Edge or Conviction

If you have genuine expertise in an area, you might tilt toward it. Factor tilts (value, momentum, quality) make sense if you have the patience to hold through multi-year underperformance. Geographic tilts make sense if you understand specific markets.

These tilts should be deliberate and sized appropriately. A 5-10% tilt to something you understand beats a 50% bet on something you're guessing about.

Consider Alternatives for Diversification, Not Returns

Alternatives should generally provide something stocks and bonds don't: different return drivers, inflation protection, or crisis performance. Adding alternatives to chase higher returns often disappoints.

Private markets make sense if you can genuinely access top-quartile managers and lock up capital for the required period. For most investors, the complexity and fees aren't worth it.

Protect Against Your Specific Risks

Someone with a concentrated stock position should consider hedging it. Someone with significant real estate should consider the correlation between their property and their financial portfolio. Someone with international business income might reduce international equity exposure.

Risk management is personal. Generic advice on diversification doesn't account for individual circumstances.

Rebalance Systematically

Choose an approach (calendar or threshold) and stick with it. Automate if possible. The discipline matters more than the specific parameters.

Final Thoughts

Investment strategies are building blocks. Some perform better in certain conditions. Some require more skill or patience. Some come with higher costs. None works all the time.

Portfolio construction is how you combine these blocks into something that serves your goals. This is where working with a qualified adviser adds value. Not someone selling a single strategy, but someone thinking holistically about your situation.

Understanding both levels is valuable. You'll make better decisions, ask better questions, and avoid expensive mistakes. The financial industry is filled with people selling their specific building block as a complete solution. Knowing the difference protects you.

The best strategy is one matched to your situation that you can actually stick with through market cycles. That sounds obvious, but it remains the thing most investors get wrong.

I write when there’s something worth sharing — playbooks, signals, and patterns I’m seeing among founders building, exiting, and managing real capital.

If that’s useful, you can subscribe here.