Before you invest seriously, you need to understand how the investment world actually works. Not the textbook version. The real one. With real incentives, real conflicts, and real costs for getting it wrong.

I've spent years working with private clients. I've watched smart people make expensive mistakes. They sat in meetings nodding along, too embarrassed to ask questions. Turns out they had no idea what was happening to their money.

Don't be that person.

Think of this as your orientation. Know the landscape before you deploy capital into it.

Key Takeaways

- The investment world runs on incentives—understand who gets paid what before you deploy capital

- Adviser fees compress with wealth: 62% charge 1%+ on $1M portfolios, but only 32% at $2M—negotiate as you scale

- Conflicts are everywhere: Even Vanguard paid $19.5M for hiding adviser incentives—always ask how your adviser gets paid

- Commission structures matter: Emerging markets pay 5–7% placement fees vs 2% in the UK—that's money leaving your pocket

- Custody is invisible until it isn't: Know where your assets actually sit—smaller firms are often sub-custodians of BNY or State Street

- Retail vs accredited isn't binary: Stay retail for core holdings (keep protections), opt into accredited for specific opportunities

- Four questions for any adviser: Do you receive commissions? Are fees tiered? What's hidden? Are you a fiduciary?

- You're not building a portfolio—you're building a system. Get the system right first.

Where the Money Comes From

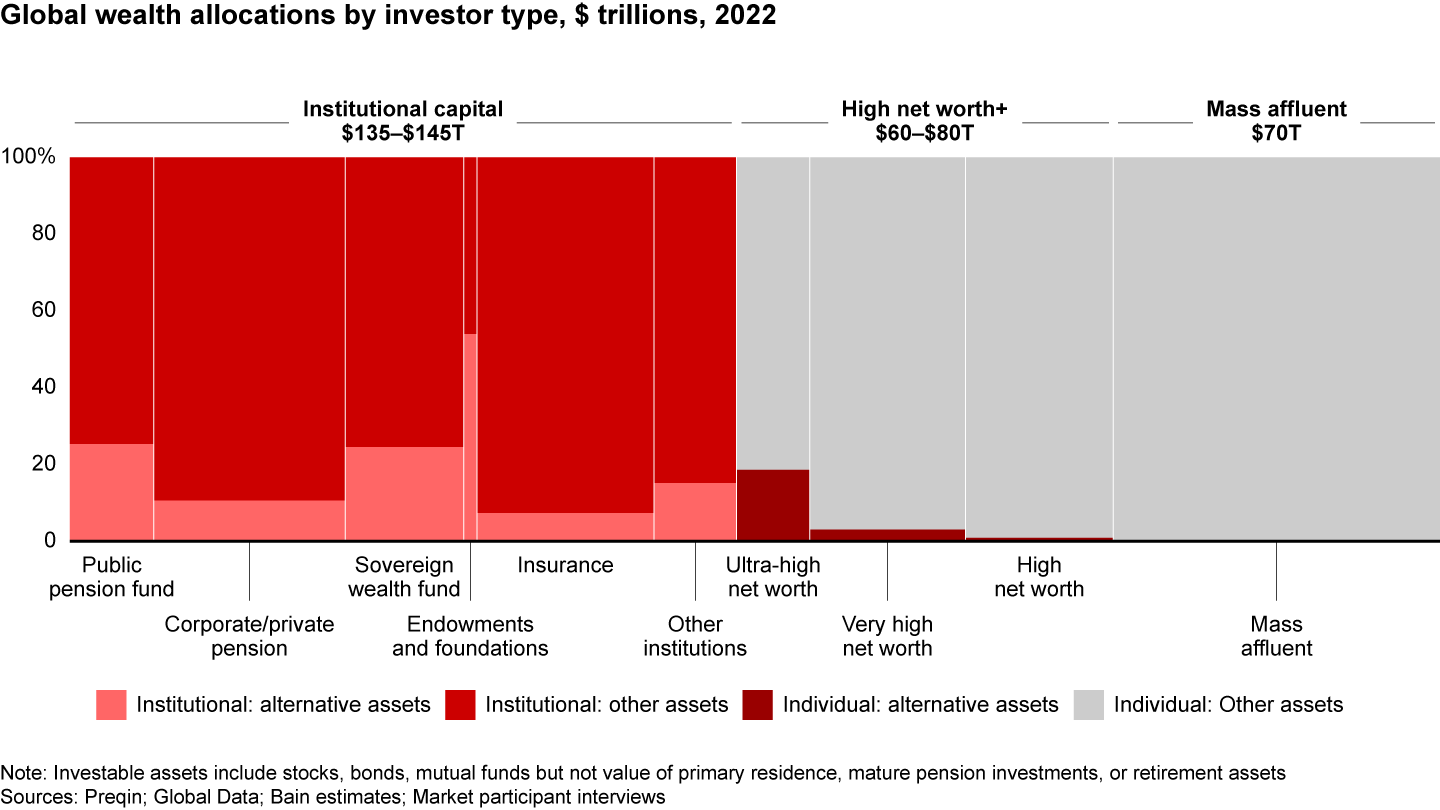

PwC's 2025 Global Asset & Wealth Management Report puts global assets under management at $139 trillion in 2024, projected to reach $200 trillion by 2030. Total investable wealth worldwide should exceed $481 trillion by decade's end.

These aren't abstract numbers. This is the pool of capital shaping markets and determining who gets rich.

Wealth comes from two sources. Institutional money flows from pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and corporations. They invest to meet long-term obligations: retirement payouts, insurance claims, and national reserves. Private wealth is money owned by individuals.

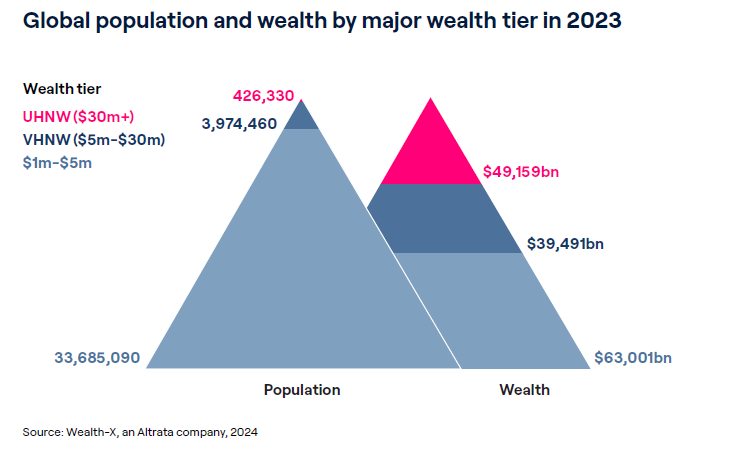

The scale is hard to grasp. Altrata's World Ultra Wealth Report 2024 counted 38.1 million people globally with at least $1 million in assets.

Of those, 426,330 have over $30 million. Together, they control $49.2 trillion. That's more than the GDP of the US and China combined.

UBS's 2025 Global Wealth Report tracks a segment they call "EMILLIs": everyday millionaires with $1–5 million. Their numbers have quadrupled since 2000. There are now 52 million of them, holding $107 trillion.

Family offices are multiplying, too. Deloitte counted 8,030 single-family offices globally in 2024. That's up 31% from 2019. They expect 10,720 by 2030.

The wealth behind these offices grew from $3.3 trillion to $5.5 trillion in five years. A 67% jump.

Despite economic chaos, the number of wealthy people continues to grow. And millions more have under $1 million sitting in bank deposits, not actively invested.

From here, we focus on private wealth and the ecosystem that manages it. Or mismanage it.

DIY or Get Help?

You have two paths.

You can do it yourself. Research investments, follow markets, and make your own calls. Some people love this. They read annual reports at night and wake up checking futures.

Or you can work with an adviser. Get professional help to avoid costly mistakes.

I think about it like this: you've been given a car but don't know how to drive. You could figure it out through trial and error. You could learn from an instructor. You could hire a driver.

The answer depends on temperament, time, and complexity. Simple portfolios can often be managed with low-cost index funds. Complex situations (business exits, multiple jurisdictions, concentrated stock positions) usually benefit from expertise.

Retail vs. Accredited

Regardless of which path you choose, you'll be classed as one of two investor types.

Retail investors get strong protections but limited access to products like hedge funds and private equity. This is the default. Even if you have $100 million.

Accredited investors get more options. Higher potential returns. Higher risks. Fewer protections.

In the US, you qualify as accredited through income ($200,000+ a year, or $300,000 with spouse), net worth ($1 million+ excluding your home), or professional credentials like Series 7, 65, or 82.

Most people don't realise you can keep your core portfolio retail while opting into accredited status for specific deals. You don't have to pick one forever.

QUICK ASK — Everything here is free. If you're finding this useful, subscribing helps me understand what's working — and keeps you updated when new pieces come out.

What Wealth Advisers Actually Do

Different advisers serve different wealth levels.

Under $3M typically means Independent Financial Advisers (IFAs) in the UK or Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) in the US. Between $3M and $30M, you're looking at wealth management firms or private banks. From $30M to $100M, multi-family (or virtual) offices become more relevant. Over $100M, single-family offices make sense as you get full control over how your wealth is managed.

That said, you can still run a family office under $100M if you want to be actively involved in investing process.

These aren't hard rules. They're guidelines reflecting economies of scale and complexity thresholds.

A good adviser develops an investment strategy and asset allocation, helps with tax planning and structuring, provides access to alternative investments, and assists with asset protection. Think of your portfolio like Lego blocks. The adviser helps to build the right structure, balance it, and swap pieces when conditions change.

How Advisers Get Paid

According to the 2024 Kitces Report, 92% of financial advisors use an assets under management (AUM) fee structure. The median is about 1% on portfolios up to $1 million, declining for larger balances.

Among advisors surveyed, 62% charge at least 1% on $1M portfolios. That drops to 32% for $2M portfolios. At higher wealth levels, some advisors charge as low as 0.25% for portfolios over $100 million.

But the fee schedule doesn't always address conflicts of interest.

Some advisers get commissions from product providers. Insurance companies. Fund managers. This isn't always bad. But you need to know about it.

In developed markets, most advisers are paid by clients. In emerging markets, commissions are common. And huge. Structured products might pay 2% in the UK but 5% to 7% elsewhere.

The problem: commissions push advisers to recommend products that pay well. Not products that serve you best. A World Economic Forum analysis was blunt: commission-based systems "undermine investors' best interests."

You might think this only happens at shady firms. It doesn't.

Vanguard paid $19.5 million to settle SEC charges for hiding conflicts. The company is built on investor-first principles. Their "salaried" advisors were getting bonuses to steer clients toward certain products. Marketing said one thing. Their incentives said another.

SEC enforcement hit 200 cases in Q1 of fiscal 2025. The highest since 2000.

I find this troubling. If Vanguard can't keep its house clean, what does that say about the rest?

Questions to ask any adviser:

Do you receive commissions or referral fees from products you recommend? What percentage do you charge on assets, and is it tiered? Are there any hidden costs, such as transaction or platform fees? Are you a fiduciary legally bound to act in my best interest?

Choosing an independent adviser paid exclusively by you helps. It doesn't eliminate conflicts entirely.

Investment Managers

Once your adviser sets a strategy, an investment manager handles day-to-day work.

Model portfolios are for retail investors. Risk profiles range from cautious to aggressive. Low fees, usually 0.1% to 0.5% a year.

Bespoke portfolios are for clients with $5 million or more. They may include hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital. Fees run up to 1% a year. Alternatives often charge "2 and 20": 2% management fee plus 20% performance fee.

Strategies differ by goal. Long-term portfolios use buy-and-hold with stocks, bonds, and ETFs. They track indices like the S&P 500. The aim is to ride out cycles while compounding.

Absolute return strategies try to make money in any market. Hedge funds use this approach. Short-selling. Derivatives. Arbitrage. They don't measure against a benchmark. Just whether they made money.

Know what you're aiming for. Growth relative to markets? Or returns that don't depend on markets? Both can live in one portfolio.

Fund Managers vs. Portfolio Managers

This confuses people because both get called "asset managers."

Fund managers run individual funds. Hedge funds, private equity, venture capital. These are building blocks.

Portfolio managers construct and monitor your overall asset allocation using third-party or in-house funds.

Large firms like Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, and UBS do both. One division runs funds. Another advises clients and manages portfolios. They also have private banks, investment banks, and brokerages under the same umbrella.

This creates structural conflicts. The firm has incentives to use its own products.

A Deloitte case study illustrated the problem: one firm's advisors invested approximately 50% of client assets in proprietary funds. They selected higher-cost share classes of their own funds while evaluating lower-cost options for competitors. The practice generated revenue for the firm. It costs clients money. And it wasn't disclosed.

Investment products come in many forms. Individual securities: stocks, bonds, options, futures. Pooled vehicles: mutual funds, ETFs, investment trusts. Alternatives: hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, real estate, commodities, crypto. Non-traditional products: actively managed certificates, structured products, exchange-traded notes.

Custody

This is the part investors never think about until something goes wrong.

Custodians safeguard your assets. They hold your securities separate from their own. They settle trades, collect dividends, handle stock splits, and meet regulatory requirements.

In October 2024, BNY became the first bank to cross $50 trillion in assets under custody. They hit $52.1 trillion.

That's not a typo. Fifty-two trillion dollars. Larger than the GDP of the US, China, and Japan combined. BNY traces back to 1784. Alexander Hamilton was one of the founders.

State Street follows with $44.3 trillion. JPMorgan and Citi round out the "big four."

Holding client money is the most regulated business in finance. If a bank is a city, custody is the fortress. The most protected part.

Smaller firms that hold client assets are usually sub-custodians. They have accounts at these giants. Your assets may sit with a boutique, but somewhere up the chain, they're held at BNY or State Street.

In the US, retail investors typically have custody at Charles Schwab, Fidelity, Pershing, LPL Financial, or Altruist. In the UK, investment platforms like Aviva, Standard Life, Quilter, AJ Bell, and JustFA serve this function.

Custodians charge 0.10% to 0.30% of assets held, plus costs for reporting, corporate actions, and transactions. Your statements should break down all fees. Read them. Fees compound against your returns.

Managed Accounts

Managed accounts separate custody from investment management. You keep assets with a trusted custodian (UBS, Goldman Sachs, Interactive Brokers) while external advisers manage investments directly in your account.

The critical point: advisers can trade on your behalf but cannot withdraw or transfer funds.

Clients keep assets secure with large institutions. Banks keep custody and earn fees. Advisers focus on strategy without building custody infrastructure.

In Switzerland, this is called External Asset Management. Clients use private banks to hold assets and for lending, but specialist advisers manage investments. It separates two functions that are often bundled together elsewhere.

Infrastructure

Behind the scenes, invisible engines power the market.

Investment banks handle underwriting, M&A advisory, and research. Brokers and prime brokers facilitate trades and provide leverage. Exchanges, market makers, and liquidity providers are where buyers meet sellers. Regulators and clearinghouses like the SEC and FCA ensure compliance and orderly settlement. Market data platforms like Bloomberg and FactSet provide the tools.

You don't need to understand every player in detail. Knowing they exist and that they all have their own incentives helps you see the whole picture.

Putting It Together

The cast of players:

Wealth owners. Institutions and individuals with money to invest.

Wealth advisers. They help you create and execute strategy.

Investment and fund managers. They manage portfolios and run funds.

Custodians. They safeguard your assets.

and The behind-the-scenes engine.

Your next steps: decide if you'll invest solo or work with an adviser, choose your investor status, build the right team, and understand fees and conflicts of interest.

You're not building a portfolio. You're building a system. Get the system right, and the portfolio takes care of itself.

I write when there’s something worth sharing — playbooks, signals, and patterns I’m seeing among founders building, exiting, and managing real capital. If that’s useful, you can subscribe here.